Image credit: Yuka Mihara (CC BY 4.0)

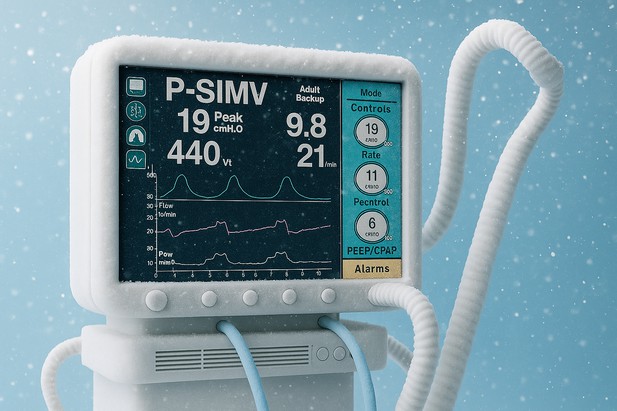

Patients suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome, a serious illness that can affect people with existing conditions, usually require ventilators to assist them with breathing. However, ongoing inflammation and changes to their conditions can complicate this breathing support, sometimes causing ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).

VILI can lead to fluid accumulation in the lungs, tissue damage and abnormally low oxygen levels in the blood. The condition has been linked to immune cells, called neutrophils, which release sticky webs as a defense against invading microorganisms. However, together with a mediator of the inflammatory immune response, the cytokine IL-1β, these neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs, can worsen inflammation and increase damage to the lungs.

Scientists have been searching for ways to mitigate this damage, and one promising strategy is therapeutic hypothermia, a controlled method of lowering body temperature. However, it has been unclear if cooling can affect the release of IL-1β and the formation of NETs.

To find out more, Nosaka et al. used a mouse model of acute respiratory distress syndrome and VILI. The researchers injected mice with lipopolysaccharide to mimic the clinical setting of ventilated patients under infection-induced septic shock, or saline solution as a control, and exposed them to high ventilation. They then measured blood pressure, blood oxygen levels and immune factors in the lung. This revealed that IL-1β boosts NET formation, which clogged the mice’s lungs and induced acute lung injury. Cooling the mice’s bodies to 32°C significantly reduced lung damage. It also lowered IL-1β levels and prevented the formation of NETs, thus protecting the lungs.

Further tests on immune cells showed that hypothermia slowed key steps in inflammation, which reduced harmful immune responses. These results suggest that lowering the body temperature could be a simple and effective way to protect lungs when ventilators are needed, which could be beneficial in the treatment of conditions such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19 or other severe lung diseases.

Therapeutic hypothermia could become an easy, non-invasive way to protect the lungs of critically ill patients and improve hospital care. However, before this treatment can be widely used, clinical trials in humans are needed to confirm its safety and effectiveness.