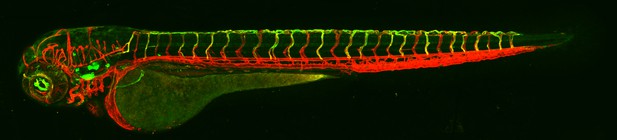

Microscopy image of a 3-day old, genetically modified zebrafish expressing a new arterial enhancer driving a green reporter gene and a pan-endothelial marker (red). Image credit: Nornes et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Our blood vessels are a biological transport system that carry oxygen and nutrients to all the cells and tissues of our bodies. Each type of blood vessel has a different structure depending on its role. For example, arteries are large, strong-walled vessels that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart into the rest of the body, while veins carry blood back to the heart and lungs once all the oxygen has been used up.

All blood vessels contain an inner lining made up of cells termed endothelial cells. These cells are also important for the formation of new blood vessels, which happens via a process called angiogenesis. During angiogenesis, the endothelial lining of new vessels forms first, by ‘sprouting’ or ‘splitting’ from the endothelial cells lining existing vessels.

We know that angiogenesis is accompanied by changes in gene activity within the new endothelial cells. For example, during the development of new arteries, endothelial cells will turn on genes involved in artery formation. These changes are controlled by biological switches, which involve special proteins (called transcription factors) and DNA sequences close to specific genes (called enhancers). When the right transcription factor interacts with an enhancer for a gene, the gene ‘switches on’.

Despite this, however, very few enhancers associated with arterial angiogenesis are known, and the mechanisms controlling this process are still poorly understood. Nornes et al. therefore set out to identify more arterial enhancers and study how they worked.

To identify potential enhancers, Nornes et al. first used computer-based analysis of the DNA surrounding eight genes known to be involved in artery formation. The enhancers were then tested in zebrafish and mice to confirm their ability to switch genes on in artery endothelial cells. These experiments revealed a set of 15 new arterial enhancers, which were tested in further biochemical and genetic studies to determine which transcription factors could interact with them. Several transcription factors previously thought to be involved in artery development did not appear to interact with any of the new enhancers.

This study sheds new light on the genetic control of blood vessel formation, in particular artery development. Nornes et al. hope that in the future the knowledge gained from these experiments will contribute to a better understanding of angiogenesis during early life, in health and disease.