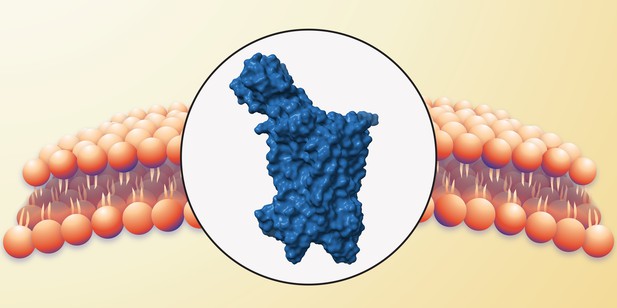

A molecular surface representation of a CCR5 chemokine receptor show in front of a cell membrane. Image credit: NIAID via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

Most promising new treatments for stroke patients face a significant challenge. Preclinical laboratory experiments on animal models may show potential, however thousands are rejected in the expensive and complicated process of human clinical trials. How should researchers design preclinical experiments to increase the chances of success in later human studies? One possible way is to match the type of evidence used by preclinical researchers with the expectations of clinicians and patients. Improving communication between these groups could ensure that preclinical studies contain experiments that are more relevant to a clinical trial setting.

With this in mind, Sharif, Jeffers et al. developed criteria for preclinical studies by analyzing multiple studies and collaborating with patient partners with lived experiences of strokes. This allowed the researchers to assess the readiness of a promising class of drugs known as CCR5 antagonists (which are already approved for medical conditions other than stroke) for clinical trials of stroke treatment.

Specifically, Sharif, Jeffers et al. screened for studies that included preclinical experiments in rats and mice that investigated the effect of CCR5 antagonists on brain recovery after stroke. From these, ten experiments which varied in the drug used, dose, and timing of treatment were compared, showing that in all cases the total area of the brain affected by stroke was reduced by the treatment. The CCR5 antagonists were also effective in treatments applied before or after a stroke event. Throughout the study the researchers worked with patient partners to assess the treatment outcomes that align with patient priorities, concluding that this factor should play a more significant role in the design of preclinical studies.

Overall, the findings show that CCR5 antagonists could represent a promising treatment for stroke patients and that future preclinical studies should involve patients and clinicians in experimental design to increase the chances of success in human trials. The proposed approach could be used in future studies when assessing which therapies should progress to human trials.