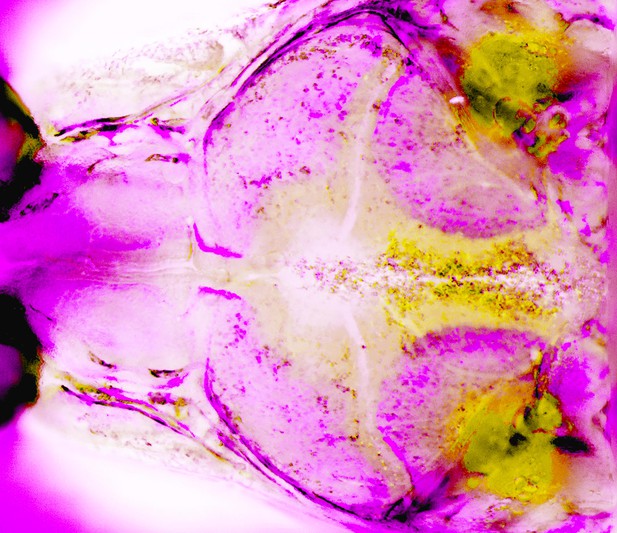

Image credit: Teng et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Some of the most common birth defects involve improper development of the head and face. One such birth defect is called craniosynostosis. Normally, an infant’s skull bones are not fully fused together. Instead, they are held together by soft tissue that allows the baby’s skull to more easily pass through the birth canal. This tissue also houses specialized cells called stem cells that allow the brain and skull to grow with the child. But in craniosynostosis these stem cells behave abnormally, which fuses the skull bones together and prevents the skull and brain from growing properly during childhood.

One form of craniosynostosis called Saethre-Chotzen syndrome is caused by mutations in one of two genes that ensure the proper separation of two bones in the roof of the skull. Mice with mutations in the mouse versions of these genes develop the same problem and are used to study this condition. Mouse studies have looked mostly at what happens after birth. Studies looking at what happens in embryos with these mutations could help scientists learn more. One way to do so would be to genetically engineer zebrafish with the equivalent mutations. This is because zebrafish embryos are transparent and grow outside their mother’s body, making it easier for scientists to watch them develop.

Now, Teng et al. have grown zebrafish with mutations in the zebrafish versions of the genes that cause Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. In the experiments, imaging tools were used to observe the live fish as they developed. This showed that the stem cells in their skulls become abnormal much earlier than previous studies had suggested. Teng et al. also showed that similar stem cells are responsible for growth of the skull in zebrafish and mice.

Babies with craniosynostosis often need multiple, risky surgeries to separate their skull bones and allow their brain and head to grow. Unfortunately, these bones often fuse again because they have abnormal stem cells. Teng et al. provide new information on what goes wrong in these stem cells. Hopefully, this new information will help scientists to one day correct the defective stem cells in babies with craniosynostosis, thus reducing the number of surgeries needed to correct the problem.