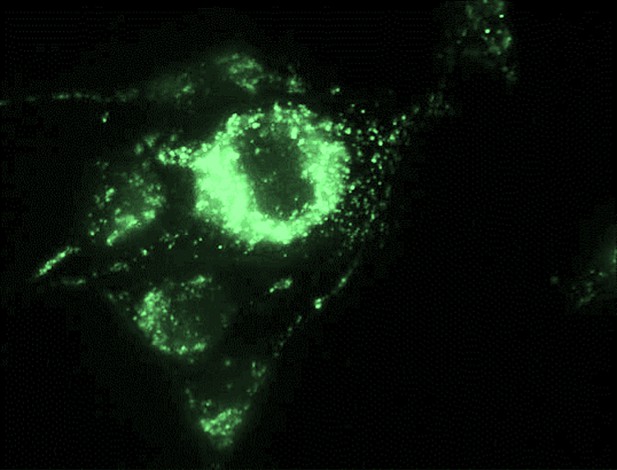

Vesicles labeled with fluorescent dye are visible as bright dots in a bone cell. Image credit: Mikolajewicz et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Athletes' skeletons get stronger with training, while bones weaken in people who cannot move or in astronauts experiencing weightlessness. This is because bone cells thrive when exposed to forces. When a bone cell is exposed to a physical force, the first thing that happens is the release of the energy-rich molecule called ATP into the space outside the cell. This molecule then binds to the neighboring cell to unleash a cascade of responses. ATP can exit the cell either through special canals in the cell membrane or released in tiny pod-like structures called vesicles. It is known that strong forces can injure the cell membrane and cause ATP to spill out. However, it is less clear how ATP is released when cells are subjected to regular forces.

Mikolajewicz et al. investigated whether ATP exits through injured membranes of cells experiencing regular forces. Bone cells grown in the laboratory were gently poked with a glass needle or placed in a turbulent fluid to simulate forces experienced in the body. Dyes and fluorescent imaging techniques were used to observe the movement of vesicles and calculate the concentration of ATP in these cells.

The experiments showed that regular forces in the body do indeed injure the cell membranes and cause ATP to spill out. But importantly, the cells repaired the injuries quickly by releasing vesicles that patch the wound. As soon as the membrane is sealed, ATP stops coming out. From the first injury, cells adapted and quickly strengthened their membrane and repair system to be more resilient against future forces. This process was also seen in the shin bones of mice.

These results are important because knowing how bone cells sense, respond and convert physical forces can help us develop treatments for astronauts, the injured and aged.