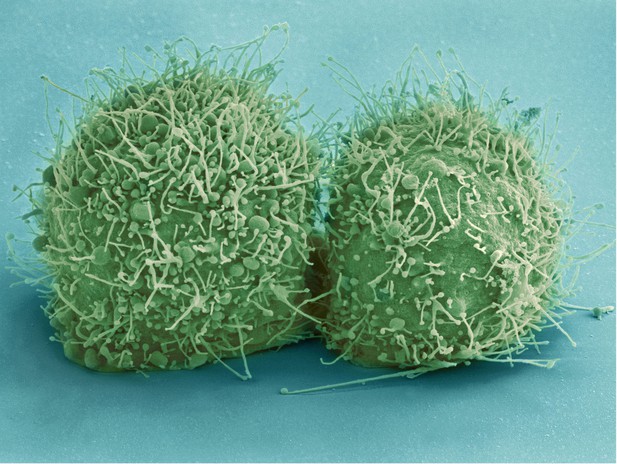

Two recently divided human cancer cells. Image credit: National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Healthy cells go through a strictly regulated process called the cell cycle in order to divide. During this cycle the cell’s DNA is duplicated and the two copies are equally distributed between the two newly formed cells. Duplicating DNA is a complex procedure that can go wrong and damage the DNA. This damage, in turn, can cause cells to stop growing or even die.

Normal cells only start replicating their DNA when there are substances known as growth factors in the environment. Without growth factors cells remain in the first phase of the cell cycle, known as G1. Most cancer cells, however, lack this ‘G1 checkpoint’ and enter the cell cycle even when growth factors are absent. This leads to DNA replication problems and damage that should cause the cells to die. Yet a characteristic of cancer cells is that they overcome these problems to grow and divide uncontrollably.

Cancer cells also often lack a protein called p53. Previous studies demonstrated that the lack of p53 helps tumor cells to survive by maintaining cell growth and reducing the likelihood of cell death. By growing cells in culture without growth factors, Benedict, van Harn et al. now show that p53 also helps cells that lack the G1 checkpoint to continue dividing.

In the experiments, cells that lacked the G1 checkpoint but still contained the p53 protein suffered from DNA replication problems and DNA damage, and subsequently died. Deleting p53 from these cells stimulated DNA replication, stopped cells from dying and helped to prevent the DNA from getting damaged. Cells could thus grow and proliferate under unfavorable conditions. Benedict, van Harn et al. also deleted p53 in tumor cells growing under the skin of mice and observed less DNA damage in these cells than in tumor cells that still have p53.

Despite reduced levels of DNA damage, the cells still had severe DNA replication problems. It is possible that these cells rely on mechanisms that allow just enough DNA replication to occur to support their proliferation. Cancer cells may therefore be highly vulnerable to drugs that interfere with these mechanisms, since they are already using them as a last resort. Future experiments will be needed to identify these mechanisms.