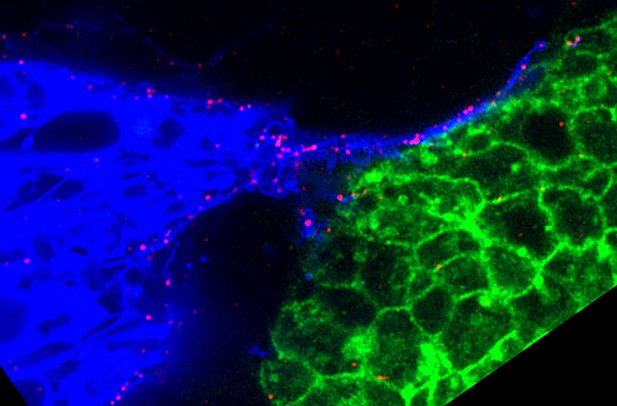

A cell (blue) can receive the signals (red) produced by its neighbor (green) through little tubes known as cytonemes. Image credit: Du et al. (CC-BY 4.0).

When an embryo develops, its cells must work together and ‘talk’ with each other so they can build the tissues and organs of the body. A cell can communicate with its neighbors by producing a signal, also known as a morphogen, which will tell the receiving cells what to do. Once outside the cell, a morphogen spreads through the surrounding tissue and forms a gradient: there is more of the molecule closer to the signaling cells and less further away. The cells that receive the message respond differently depending on how much morphogen they get, and therefore on where they are placed in the embryo.

How morphogens move in tissues to create gradients is still poorly understood. One hypothesis is that, once released, they spread passively through the space between cells. Instead, recent research has shown that some morphogens travel through long, thin cellular extensions known as cytonemes. These structures directly connect the cells that produce a morphogen with the ones that receive the molecule. Yet, it is still unclear how cytonemes can help to form gradients.

Du et al. aimed to resolve this question by following a morphogen called Branchless as it traveled through fruit fly embryos. Branchless is important for sculpting the embryonic airway tissue into a delicate network of branched tubes which supply oxygen to the cells of an adult fly. However, no one knew how cells communicate Branchless, whether or not Branchless formed a gradient, and if it did, how this gradient was created to set up the plan to form airway tubes. It was assumed that the molecule would diffuse passively to reach airway cells – but this is not what the experiments by Du et al. showed.

To directly observe how Branchless moves among cells, insects were genetically engineered to produce Branchless molecules attached to a fluorescent ‘tag’. Microscopy experiments using these flies revealed that Branchless did not diffuse passively; instead, airway cells used cytonemes to ‘reach’ towards the cells that produced the molecule, collecting the signal directly from its source. The gradient was created because the airway cells near the cells that make Branchless had more cytonemes, and therefore received more of the molecule compared to the cells that were placed further away. Genetic analysis of the airway tissue showed that Branchless acts as a morphogen to switch on different genes in the receiving cells placed in different locations. The target genes activated by the gradient instruct the receiving cells on how many cytonemes need to be extended, which helps the gradient to maintain itself over time.

Du et al. demonstrate for the first time how cytonemes can relay a signal to establish a gradient in a developing tissue. Dissecting how cells exchange information to create an organism could help to understand how this communication fails and leads to disorders.