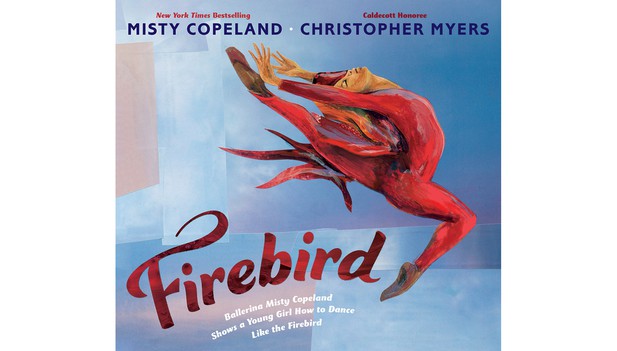

Image credit: Gilda N. Squire – Squire Media & Management, Inc. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Although most of us will never achieve the grace and dexterity of professional ballerina Misty Copeland, we each make sophisticated, complex movements every day. Even simple movements often involve coordinating many muscles throughout the body. Moreover, because we have so many muscles, there are often multiple ways that we could use them to make the same movement. So which ones do we use, and why?

Many studies into muscle control focus on how the muscles activate to perform a task like kicking a soccer ball. But muscles do more than just move the limbs; they also act on joints. Contracting a muscle exerts strain on bones and the ligaments that hold joints together. If these strains become excessive, they may cause pain and injury, and over a longer time may lead to arthritis. It would therefore make sense if the nervous system factored in the need to protect joints when turning on muscles.

The quadriceps are a group of muscles that stretch along the front of the thigh bone and help to straighten the knee. To investigate whether the nervous system selects muscle activations to avoid joint injuries, Alessando et al. studied rats that had one particular quadriceps muscle paralyzed. The easiest way for the rats to adapt to this paralysis would be to increase the activation of a muscle that performs the same role as the paralyzed one, but places more stress on the knee joint. Instead, Alessando et al. found that the rats increase the activation of a muscle that minimizes the stress placed on the knee, even though this made it more difficult for the rats to recover their ability to use the leg in certain tasks.

The results presented by Alessando et al. may have important implications for physical therapy. Clinicians usually work to restore limb movements so that a task is performed in a way that is similar to how it was done before the injury. But sometimes repairing the damage can change the mechanical properties of the joint – for example, reconstructive surgery may replace a damaged ligament with a graft that has a different strength or stiffness. In those cases, performing movements in the same way as before the surgery could place abnormal stress on the joint. However, much more research is needed before recommendations can be made for how to rehabilitate rats after injury, let alone humans.