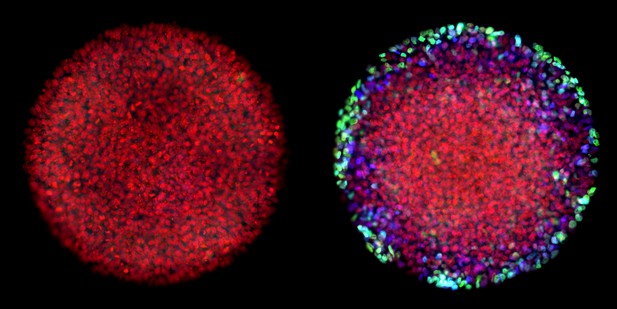

ACTIVIN causes stem cells to specialize to form germ layers (blue and green) following exposure to WNT. Image credit: Yoney et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Embryonic stem cells can renew themselves to generate more stem cells, or specialize to become any type of cell found in an adult. They therefore hold great potential for studying how we develop from a single cell into a complex organism made of many different cell types.

In a key stage of development, individual cells form into organized tissues. The earliest phase of tissue organization involves the formation of three ‘germ layers’. Human embryonic stem cells allow us to recreate this early stage of embryo development in the lab. When grown in confined spaces, the cells organize into clusters that can then develop germ layers. Previous work using these clusters showed that a network of signaling proteins – including one called WNT – trigger human embryonic stem cells to form the initial clusters. Then, another signaling protein called ACTIVIN tells the cells to specialize to form the two inner germ layers. But in experiments that apply only the ACTIVIN signal, the cells instead keep dividing to make more stem cells.

ACTIVIN can trigger the activity of a protein called SMAD. To visualize how cells respond to ACTIVIN in real time, Yoney et al. used a gene editing technique called CRISPR to add fluorescent tags to SMAD in human embryonic stem cells. The results show that the ACTIVIN response triggers a peak in the amount of SMAD in the cell’s nucleus that then decreases over several hours. This briefly activated several genes that are known to help to form germ layers. However, this gene activity was not maintained for long enough to cause the stem cells to specialize and organize into layers.

Yoney et al. then repeated the experiments on cells that had previously been exposed to WNT signaling proteins. The germ layer gene activity was maintained in this case, leading to the cells specializing and forming the inner two germ layers. This suggests that the cells somehow remembered the WNT signal, and this memory changed how they responded to ACTIVIN.

The next step is to understand how cells store the memory of the WNT signal. As well as aiding our understanding of development, it could also help us to understand situations where signaling goes wrong, such as cancer. The technique used here to follow signals in real time could also be used to study other biological signaling processes.