Image credit: Andy Peters (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

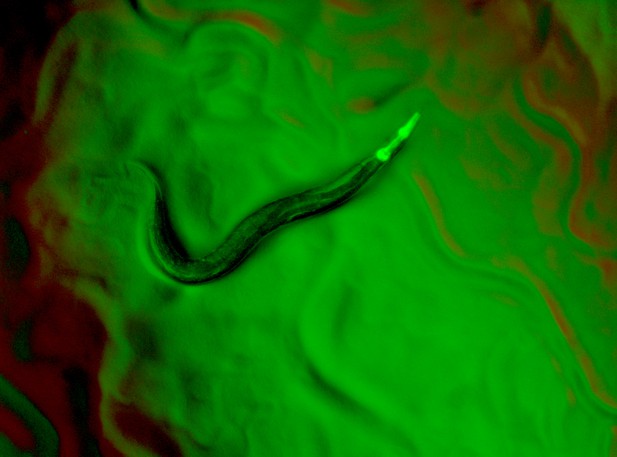

Aging may seem inescapable, but there are many factors, from diet to genetic mutations, that can affect this process. In fact, scientists have started to uncover the mechanisms that control and influence this slow decline. For example, in the small worm Caenorhabditis elegans, removing the germs cells – which give rise to eggs – extends the lifespan. Similarly, interfering with the activity of the Insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway leads to a longer life for the animals. However, it is unclear whether these two mechanisms work together, or if they operate in parallel.

To explore this, Moll, Roitenberg et al. first looked at how the IIS pathway regulates a type of protein modification known as SUMOylation in C. elegans. Reducing the activity of the IIS pathway slowed down aging in the worms. It also decreased the levels of SUMOylation of certain proteins, including CAR-1, which is found in the structures that produce germ cells. Further experiments showed that stopping the SUMOylation of CAR-1 extended the lifespan of the animals. In fact, replacing the protein with a mutated version of CAR-1 that cannot accept the SUMO element makes the worms live longer and resist a toxic protein that causes Alzheimer’s disease in humans. These results therefore show that, in C. elegans, the IIS pathway and a mechanism that involves CAR-1 in germ cells work together to determine the pace of aging. Further studies are now needed to dissect how the IIS pathway influences SUMOylation, and whether the findings hold true in mammals.