Image credit: Sun et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Some insects have a sense – called hygroreception – that allows them to detect changing levels of moisture in the air. These insects use this sense to avoid becoming too dry, or to find food or places to lay their eggs. In many species, including the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the antennae are important for hygroreception. Cells in the antennae produce lots of small proteins called odorant binding proteins, or Obps for short. These proteins are believed mostly to help the antennae to detect various chemical signals in the air, but it was not known if any of these proteins were also involved in hygroreception.

Obp59a is an odorant binding protein that is found in the parts of the antennae that sense moisture, and Sun et al. set out to establish whether it has a role in hygroreception in the fruit fly. A closer look confirmed that Obp59a proteins were indeed found specifically in the moisture-sensitive parts of the antennae, the hygroreceptive sensilla. Further experiments showed that flies without Obp59a could not respond properly to changing humidity over periods of seconds, minutes and hours. These results indicated that Obp59a is important for insect hygroreception.

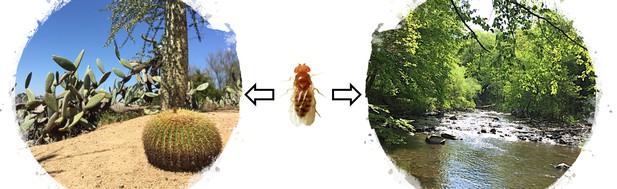

Perhaps unexpectedly, these mutant flies were also more resistant to drying out. Sun et al. suggest that, because flies without Obp59a struggle with hygroreception, they may also become more cautious to avoid becoming too dry. Further experiments could now test this hypothesis. Since insects like mosquitoes use hygroreception to find their human hosts or choose where to lay their eggs, Obp59a may become a useful target for controlling insect-borne infections. Also, understanding insect hygroreception may yield new insights into how climate change will affect insect populations around the world.