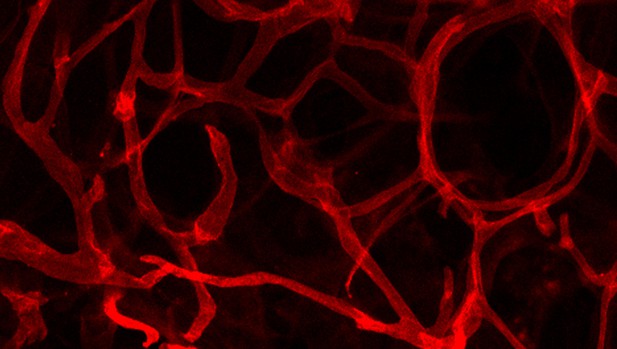

The capillaries (in red) inside a fat tissue. Image credit: Emilie Roudier (CC BY 4.0)

In the body, thread-like blood vessels called capillaries weave their way through our tissues to deliver oxygen and nutrients to every cell. When a tissue becomes bigger, existing vessels remodel to create new capillaries that can reach far away cells. However, in obesity, this process does not happen the way it should: when fat tissues expand, new blood vessels do not always grow to match. The starved fat cells can start to dysfunction, which causes a range of issues, from inflammation and scarring of the tissues to problems with how the body processes sugar and even diabetes. Yet, it is still unclear why exactly new capillaries fail to form in obesity.

What we know is that a protein called FoxO (short for Forkhead box O) is present in the cells that line the inside of blood vessels, and that it can stop the development of new capillaries. FoxO controls how cells spend their energy, and it can force them to go into a resting state. During obesity, the levels of FoxO actually increase in capillary cells. Therefore, it may be possible that FoxO prevents new blood vessels from growing in the fat tissues of obese individuals.

To find out, Rudnicki et al. created mice that lack the FoxO protein in the cells lining the capillaries, and then fed the animals a high-fat diet. These mutant mice had more blood vessels in their fat tissue, and their fat cells looked healthier. They also stored less fat than normal mice on the same diet, and their blood sugar levels were normal. This was because the FoxO-deprived cells inside capillaries were burning more energy, which they may have obtained by pulling sugar from the blood.

These results show that targeting the cells that line capillaries helps new blood vessels to grow, and that this could mitigate the health problems that arise with obesity, such as high levels of sugar (diabetes) and fat in the blood. However, more work is needed to confirm that the same cellular processes can be targeted to obtain positive health outcomes in humans.