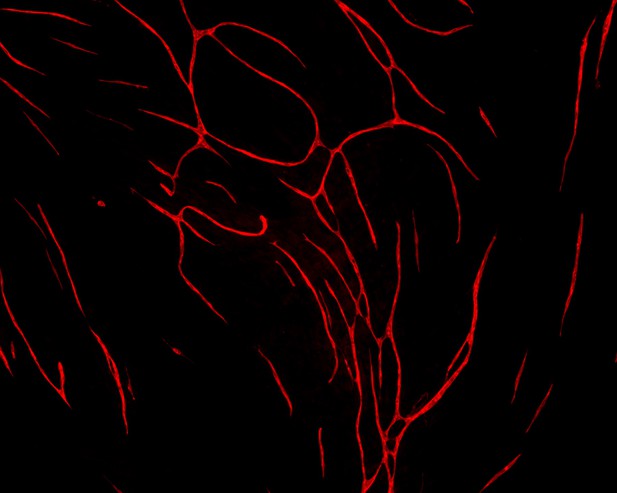

Formation of blood vessels. Image credit: Zhou et al. 2019 (CC BY 4.0)

A well-networked supply of blood vessels is essential for delivering nutrients and oxygen to the body. To do so, new blood vessels need to form throughout life, from embryonic development to adult life. This process, known as angiogenesis, also plays a critical role in exercise, menstruation, injury and disease.

If it becomes faulty, it can lead to conditions such as the ‘wet’ version of age-related macular degeneration, where leaky blood vessels grow under the retina. This can lead to rapid and severe loss of vision. One way to treat this condition is to stop the growth of new blood vessels into this area using anti-angiogenic therapy, but not all patients respond to it. Identifying new mechanisms at play in human angiogenesis could provide insight into potential new therapies for this disease and other angiogenesis-related conditions.

A large amount of our genetic material is made up of a group of molecules called long non-coding RNAs or lncRNAs for short, which normally do not code for proteins. However, they are thought to play a role in many processes and diseases, but it has been unclear if they also influence angiogenesis. Now, Zhou, Yu et al. set out to study these RNA molecules in different types of human vessel-lining cells and to identify their role in angiogenesis.

Out of the 30,000 lncRNAs measured, about 500 of them were more abundant in these cells than other types of cells. One of the lncRNAs, called lncEGFL7OS, can be found on two human genes known to be relevant in angiogenesis (EGFL7 and miR-126). The results showed that patients with a condition called dilated cardiomyopathy, in which the heart muscle overstretches and becomes weak, had elevated levels of lncEGFL7OS. Other experiments analyzing human eye tissue revealed that lncEGFL7OS is required for angiogenesis by increasing the concentration of the EGFL7 and miR-126 gene products in cells. To achieve this, it binds together with a specific protein to the regulatory regions of the two genes to control their activity.

The discovery of a new control mechanism for angiogenesis in humans could lead to new therapies for conditions such as macular degeneration and other diseases in which angiogenesis is affected. A next step will be to see if the same RNA molecules and genes are also elevated in other diseases.