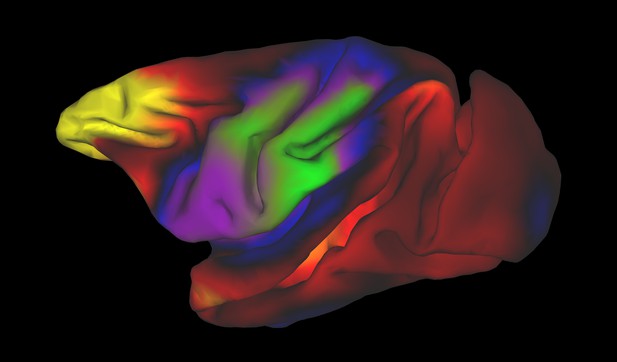

Ultrasound can alter brain activity in a precise way. Image credit: Verhagen, Gallea et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Ultrasound is well known for making visible what is hidden, for example, when giving parents a glimpse of their child before birth. But researchers are now using these high-frequency sound waves – beyond the range of human hearing – for a wholly different purpose: to manipulate the activity of the brain. Conventional brain stimulation techniques use electric currents or magnetic fields to alter brain activity. These techniques, however, have limitations. They can only reach the surface of the brain and are not particularly precise. By contrast, beams of ultrasound can be focused at a millimetre scale, even deep within the brain. Ultrasound thus has the potential to provide new insights into how the brain works.

Most studies of ultrasound stimulation have looked at what happens to the brain during the stimulation itself. But could ultrasound also induce longer-lasting changes in brain activity? Changes that persist after the stimulation has ended would be valuable for research. They would also make it more likely that we could use ultrasound to treat brain disorders by changing brain activity.

Verhagen, Gallea et al. used a brain scanner to measure brain activity in macaque monkeys after ultrasound stimulation. The results showed that 40 seconds of repetitive ultrasound changed brain activity for up to two hours. Ultrasound caused the stimulated brain area to interact more selectively with the rest of the brain. Notably, only the stimulated area changed its activity in this way. This helps rule out the possibility that the changes reflect non-specific effects. If the monkeys had been able to hear the ultrasound, for example, it would have changed the activity of the parts of the brain related to hearing. Most important of all, the changes were reversible and did not harm the brain.

The results of Verhagen, Gallea et al. show that repetitive ultrasound can induce long-lasting alterations in brain activity. It can target areas deep within the brain, including those that are out of reach with other techniques. If this procedure also shows longer-lasting effects in people, it could yield valuable insights into the links between brain and behaviour. It could also help us develop new treatments for neurological and psychiatric disorders.