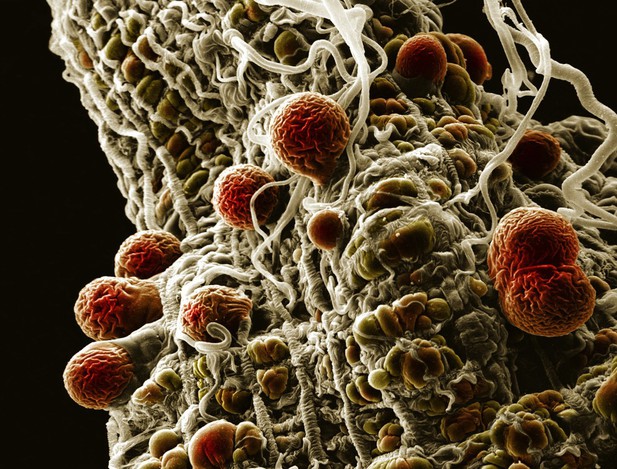

Oocysts of the parasite that causes rodent malaria (Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis) developing on the midgut wall of the mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Image credit: Hilary Hurd (CC BY-NC)

The global burden of malaria has decreased over the last decade. Many countries now aim to banish malaria. One obstacle to elimination is people who carry malaria parasites without showing symptoms. These asymptomatic people are unlikely to be diagnosed and treated and may contribute to further spread of malaria. One way to clear all malaria infections would be to ask everyone in a community to take antimalarial drugs at the same time, even if they do not feel ill. This tactic is most likely to work in communities that are already reducing malaria infections by other means. For example, by treating symptomatic people and using bed nets to prevent bites from malaria-infected mosquitos.

Several studies have shown that mass drug administration is a promising approach to reduce malaria infections. But its success depends on enough people participating. If enough community members take antimalarial drugs, then even those who cannot participate, such as young children or pregnant women, should be less likely to get malaria. This is called the herd effect.

Now, Parker et al. demonstrate that mass antimalarial drug administration reduces infections with malaria caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. The analysis looked at malaria infections among residents of four villages in the Kayin State of Myanmar that used mass antimalarial drug administration. People who lived in neighborhoods with high participation in mass drug administration were almost three times less likely to get malaria than people who lived in communities with low participation. Even people who did not take part benefited.

The analysis suggests that mass antimalaria drug administration benefits individuals and their communities if enough people take part. To be successful, malaria elimination programs that wish to use mass drug administration should approach communities in a way that encourages high levels of participation.