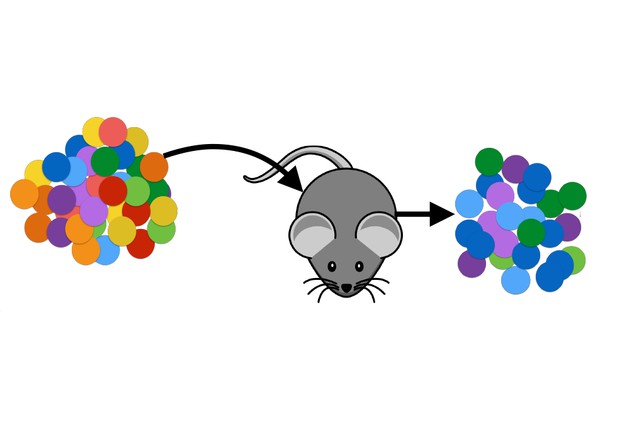

A cocktail of cancerous cells, each carrying a different antigen (multiple colors) is injected into a mouse. The resulting tumor is made of cells that managed to evade the immune system. Image credit: Adapted from Gejman, Chang et al. (CC BY 4.0)

T cells are specialized agents of the immune system that can detect and attack tumors. They spot their target by identifying small pieces of proteins – or antigens – at the surface of diseased cells. In particular, they can recognize the new and abnormal antigens that a cancer cell often displays. Yet, cells that become cancerous and start displaying suspicious antigens can manage to escape T cells and grow into full tumors. Why does the immune system not recognize and kill these early cancers before they get out of control?

One possibility is that T cells do not identify certain antigens carried by cancer cells. To test this, researchers have conducted experiments where they inject a mouse with cancer cells that display a single new antigen. If the animal develops a tumor, then this antigen does not trigger an immune response. However, this method is slow and laborious, because only one antigen can be tested at the time. Instead, Gejman, Chang et al. developed a new technique, PresentER, where a rodent gets injected with a mix of millions cancer cells that each displays a different antigen. This way, many thousands of new antigens can be studied in one go. The tumors are left to grow for several weeks before they are removed and analyzed to see which cells survived and which have been killed by the immune system.

Unexpectedly, the nature of the antigen did not make a big difference. Instead, cancer cells with new antigens could go undetected if they were rare and made up only a small proportion of all the different cancer cells in a tumor. However, the immune system would eliminate the exact same cancer cells when they were the major component of a cancerous lump.

Future research now has to explore exactly how rare cancer cells can hide amongst other cells, and remain invisible to the body. Armed with this knowledge, it might be possible to improve cancer therapy by prompting the immune system to target these emerging threats earlier.