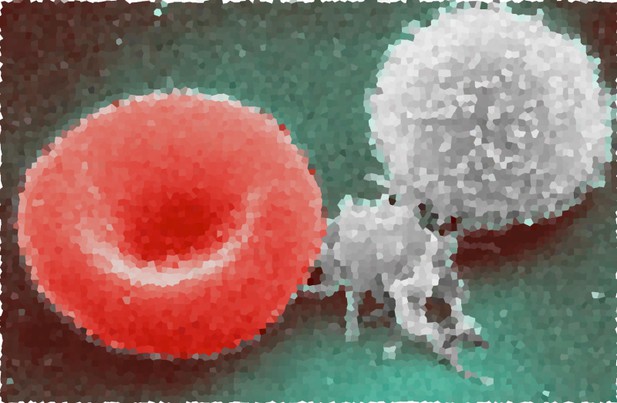

A red blood cell, a platelet and white blood cell. Image credit: Public domain

As far as we know, all adult blood cells derive from blood stem cells that are located in the bone marrow. These stem cells can produce red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets – the cells fragments that form blood clots to stop bleeding. They can also regenerate, producing more stem cells to support future blood cell production. But, our understanding of the system may be incomplete.

The easiest way to study blood cell production is to watch what happens after a bone marrow transplant. Before a transplant, powerful chemotherapy kills the existing stem cells. This forces the transplanted stem cells to restore the whole system from scratch, allowing scientists to study blood cell production in fine detail. But completely replacing the bone marrow puts major stress on the body, and this may alter the way that the stem cells behave. To understand how adult stem cells keep the blood ticking over on a day-to-day basis, experiments also need to look at healthy animals.

Säwén et al. now describe a method to follow bone marrow stem cells as they produce blood cells in adult mice. The technique, known as lineage tracing, leaves an indelible mark, a red glow, on the stem cells. The cells pass this mark on every time they divide, leaving a lasting trace in every blood cell that they produce. Tracking the red-glowing cells over time reveals which types of blood cells the stem cells make as well as provides estimates on the timing and extent of these processes.

It has previously been suggested that a few types of specialist blood cells, like brain-specific immune cells, originate from cells other than adult blood stem cells. As expected, the adult stem cells did not produce such cells. But, just as seen in transplant experiments, the stem cells were able to produce all the other major blood cell types. They made platelets at the fastest rate, followed by certain types of white blood cells and red blood cells. As the mice got older, the stem cells started to slow down, producing fewer blood cells each. To compensate, the number of stem cells increased, helping to keep blood cell numbers up.

This alternative approach to studying blood stem cells shows how the system behaves in a more natural environment. Away from the stresses of transplant, the technique revealed that blood stem cells are not immune to aging. In the future, understanding more about the system in its natural state could lead to ways to boost blood stem cells as we get older.