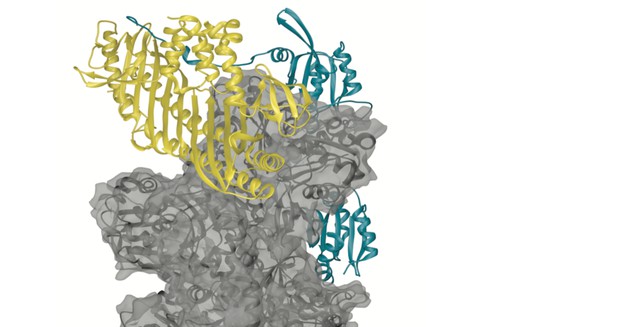

Possible complex formed by Twinfilin (blue), Capping Protein (yellow) and the end of an actin filament (gray). Image credit: Johnston et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Plant and animal cells are supported by skeleton-like structures that can grow and shrink beneath the cell membrane, pushing and pulling on the edges of the cell. This scaffolding network – known as the cytoskeleton – contains long strands, or filaments, made from many identical copies of a protein called actin. The shape of the actin proteins allows them to slot together, end-to-end, and allows the strands to grow and shrink on-demand. When the strands are the correct length, the cell caps the growing ends with a protein known as Capping Protein. This helps to stabilize the cell’s skeleton, preventing the strands from getting any longer, or any shorter.

Proteins that interfere with the activity of Capping Protein allow the actin strands to grow or shrink. Some, like a protein called V-1, attach to Capping Protein and get in the way so that it cannot sit on the ends of the actin strands. Others, like CARMIL, bind to Capping Protein and change its shape, making it more likely to fall off the strands. So far, no one had found a partner that helps Capping Protein limit the growth of the actin cytoskeleton.

A protein called Twinfilin often appears alongside Capping Protein, but the two proteins seemed to have no influence on each other, and had what appeared to be different roles. Whilst Capping Protein blocks growth and stabilizes actin strands, Twinfilin speeds up their disassembly at their ends. But Johnston, Hilton et al. now reveal that the two proteins actually work together. Twinfilin helps Capping Protein resist the effects of CARMIL and V-1, and Capping Protein puts Twinfilin at the end of the strand. Thus, when Capping Protein is finally removed by CARMIL, Twinfilin carries on with disassembling the actin strands.

The tail of the Twinfilin protein looks like part of the CARMIL protein, suggesting that they might interact with Capping Protein in the same way. Attaching a fluorescent tag to the Twinfilin tail revealed that the two proteins compete to attach to the same part of the Capping Protein. When mouse cells produced extra Twinfilin, it blocked the effects of CARMIL, helping to grow the actin strands. V-1 attaches to Capping Protein in a different place, but Twinfilin was also able to interfere with its activity. When Twinfilin attached to the CARMIL binding site, it did not directly block V-1 binding, but it made the protein more likely to fall off.

Understanding how the actin cytoskeleton moves is a key question in cell biology, but it also has applications in medicine. Twinfilin plays a role in the spread of certain blood cancer cells, and in the formation of elaborate structures in the inner ear that help us hear. Understanding how Twinfilin and Capping Protein interact could open paths to new therapies for a range of medical conditions.