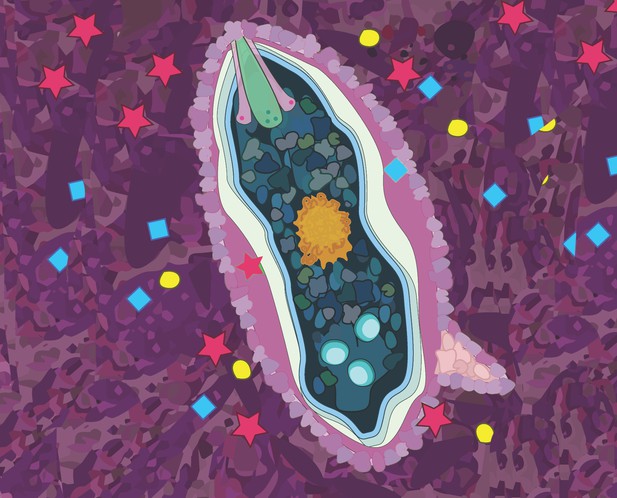

S. mansoni eggs (structure at the center) release several proteins (blue squares, yellow circles) in the human body, including omega-1 ribonuclease (red stars). Image credit: Ittiprasert et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Schistosomiasis is a tropical disease that can cause serious health problems, including damage to the liver and kidneys, infertility and bladder cancer. Nearly a quarter billion people are currently infected, mostly in poor regions of sub-Saharan Africa, the Philippines and Brazil.

A freshwater worm known as Schistosoma mansoni causes the disease. These parasites enter the human body by burrowing into the skin; once in the bloodstream, they move to various organs where they rapidly start to reproduce. Their eggs release several molecules, including a protein known as omega-1 ribonuclease, which can damage the surrounding tissues.

A gene editing technique called CRISPR/Cas9 allows scientists to precisely target and then deactivate the genetic information a cell needs to produce a given protein. While the tool has been used in other species before, it was unknown if it could be applied to S. mansoni. Here, Ittiprasert et al. harnessed CRISPR/Cas9 to deactivate the gene that codes for omega-1 ribonuclease and create parasites that do not produce the protein, or only very little of it. The experiments showed that mice infected with the gene-edited worm eggs displayed far fewer symptoms of schistosomiasis compared to those that carry the non-edited parasites.

Alongside this work, Arunsan et al. used CRISPR/Cas9 to inactivate a gene in another species of worm that can cause liver cancer in humans. Together, these findings demonstrate for the first time that the gene editing method can be adapted for use in parasitic flatworms, which are a major public health problem in tropical climates. This tool should help scientists understand how the parasites invade and damage our bodies, and provide new ideas for treatment and disease control.