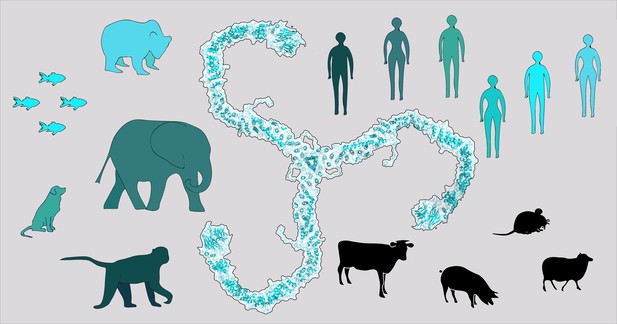

CHC22 – a “three-legged” protein – has changed over evolutionary time. Some animals, including humans, carry different variants of the protein (shaded in blues and green); while others (black) no longer use it. Image credit: Marine Camus and Jeremy Wilbur (CC BY 4.0)

When we eat carbohydrates, they are digested into sugars that circulate in the blood to provide energy for the brain and other parts of the body. But too much blood sugar can be poisonous. The body regulates blood sugar balance using the hormone insulin, which triggers the removal of sugar from the blood into muscle and fat cells. This removal process involves a pore in membranes at the surface of muscle and fat tissue, called a glucose transporter, through which the sugar molecules can pass. During fasting, the glucose transporter remains inside muscle and fat. But after a meal, insulin acts to release the transporter from its storage area to the surface of the tissue. How efficiently this process happens reflects how efficiently sugar can be removed from the blood. When this pathway breaks down, it can lead to diabetes.

In humans, a protein called CHC22 is needed to deliver the glucose transporter to its storage area. In mice, CHC22 is absent. The question arises: do different animals' eating habits influence CHC22's role in controlling blood sugar? The evolutionary history of CHC22 in a number of different animals could reveal what is special about glucose transport after a meal in humans, and how it might fail in diabetes.

By analyzing the genomes of several different species, Fumagalli et al. found that the gene encoding CHC22 first evolved around the time animals began developing a backbone and complex nervous systems. Afterwards, it was lost by some animals – including mice, sheep and pigs. Fumagalli et al. also discovered that CHC22 varies between individual people. A new form of CHC22, which first appeared in ancient humans, is less effective at holding the glucose transporter inside muscle and fat – leading to a tendency to reduce blood sugar levels. This new form became more common in humans over a period witnessing the introduction of cooking, and later farming; both of these technologies are associated with increased sugar in the diet. But not everyone has this new variant of the gene – both the old and newer variants are present in people today.

The history of CHC22 suggests that it was useful for early humans to hold the glucose transporter inside muscle and fat, keeping blood sugar levels high, which contributed to the development of a large brain. But as humans became exposed to higher dietary levels of sugar the newer form of CHC22 allowed blood sugar to be lowered more readily. People with different forms of CHC22 are likely to differ in their ability to control blood sugar after a meal. In some cases, this could lead to heightened blood sugar levels, which in turn can lead to diabetes.