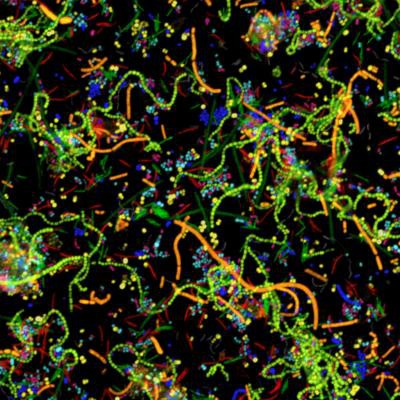

Fluorescent image of 15 different species of human oral microbes grown in the laboratory. Image credit: Alex Valm (CC BY 4.0)

Trillions of bacteria and other microbes live in the human body. The mouth and the gut in particular, are microbial hot spots at either end of the digestive tract. Every day, humans swallow around 1.5 liters of saliva, along with millions of oral microbes. Scientists believe that more than 99% of these microbes die as they pass through the acidic environment of the stomach and later the small intestine, which act as a barrier between the bacteria of the mouth and gut.

Failure of this barrier can lead to overgrowth of oral microbes in the gut. This may contribute to diseases like bowel cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases. But even in healthy people, low levels of microbes usually found in the mouth are often found in stool. It is unclear if these microbes cross the barrier or if they are similar microbes that originate in the gut.

Now, Schmidt, Hayward et al. show that in healthy people at least one in three oral microbial cells pass through the digestive tract to settle the gut in healthy people. This challenges the notion of a mouth-gut barrier. In the experiments, the genetic material of all the microbes in the saliva and stool of several hundred people from three continents was analyzed. This allowed Schmidt, Hayward et al. to determine whether strains found in the gut originate from the mouth, or are closely related but specialized gut types of the same species. The results also showed that patients with bowel cancer and rheumatoid arthritis had more mouth-to-gut microbial transmission than their healthy counterparts.

The experiments suggest that the mouth is a microbial reservoir that constantly replenishes the gut flora. Some of the gut-traveling oral bacteria trigger inflammation when they grow in other parts of the body like the lining of the heart. This, along with the discovery that patients with certain diseases have more oral bacteria in the gut, may suggest that the transmission of these microbes contributes to disease. The experiments also indicate that finding ways to influence oral bacteria might affect the ones in the gut. More studies are needed to understand how mouth microbes survive the trip to the gut and are able to thrive in this competitive environment, and what role they play in health and disease.