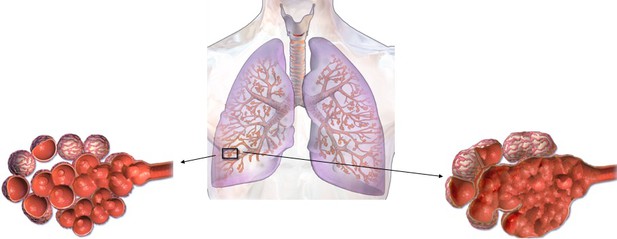

Schematic representing healthy alveoli (left) and alveoli with emphysema (right). Image credit: Modified from Blausen Medical Communications, Inc. (CC BY 3.0)

It is well known that smoking is bad for the lungs. Not only can smoking cause lung cancer, it can also lead to conditions such as emphysema. This is the gradual damage to lung tissue that occurs when the walls of the tiny air-sacs in the lungs where the blood takes up oxygen, called the alveoli, weaken and break. Emphysema causes shortness of breath and difficulty pushing air out of the lungs, and it is part of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (also known as COPD).

Genetic differences mean that certain people are more likely to develop emphysema than others. As an example, if someone has genetic mutations that alter the activity of a gene called TGFB2, their risk of developing emphysema increases. However, the specific genetic mutations that modify the activity of TGFB2 were previously unknown.

Parker et al. analyzed the genetic sequences of TGFB2 from patients with emphysema and compared them to those from healthy individuals. This revealed that certain mutations near the TGFB2 gene were more common in patients with emphysema. Next, Parker et al. showed that, in healthy lung cells called fibroblasts, the stretch of DNA that was mutated in patients with emphysema touched the part of TGFB2 that controls when the gene is activated. Deleting that same stretch of DNA in the fibroblasts meant the cells could no longer activate the TGFB2 gene as efficiently. Together, these results reveal a genetic difference that increases the risk for emphysema.

COPD affects approximately 175 million people worldwide, causing over three million deaths each year. The findings of Parker et al. suggest that developing drugs that safely and efficiently target TGFB2 may be a way to help patients with early signs of emphysema.