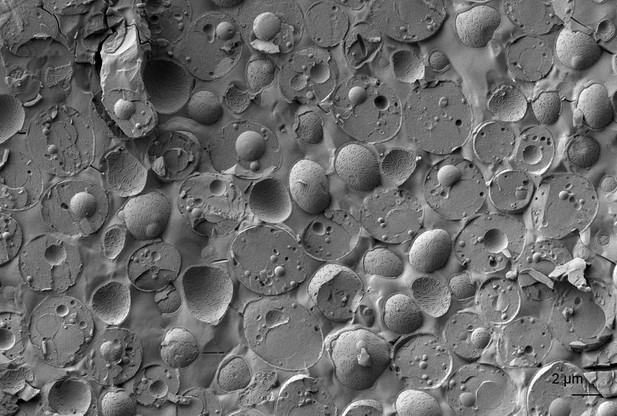

When yeast cells divide, they must create more ribosomes, the machinery that pieces together proteins. Image credit: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Wanner, LMU Munich, Faculty of Biology (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Cells are made up of thousands of different proteins that perform unique roles required for life. To create all of these proteins, cells use machines called ribosomes that are partly formed of elements known as r-proteins. When cells grow and divide, the ribosomes have to make copies of themselves through a process called ribosome biogenesis.

Although all cells need ribosomes, certain types of cells are especially sensitive to events that interfere with ribosome biogenesis. For example, patients that have mutations in genes needed for ribosome biogenesis produce fewer red blood cells, but their other cells and tissues are mostly healthy. It is not clear why some cells are more sensitive than others.

Ribosome biogenesis is very similar between different organisms, so researchers often use budding yeast as a model to study the process. Here, Tye et al. used genetic and chemical tools to interfere with ribosome biogenesis on short time scales, which made it possible to detect early on what was going wrong in the cells.

The experiments found that when ribosome biogenesis was disrupted, r-proteins that were waiting to be assembled into ribosomes quickly stuck to one another and formed clumps that reduced the ability of the yeast cells to grow. The cells responded by switching on a protein called Hsf1, which restored their ability to grow. Yeast cells that were growing quickly, and therefore making more ribosomes, were more sensitive to abnormal ribosome biogenesis than slow-growing cells.

These results indicate that how actively a cell is growing, and its ability to cope with r-proteins sticking together, may in part explain why certain cells are more vulnerable to events that interfere with ribosome biogenesis. Since human cells also have Hsf1, future experiments could investigate whether turning it on might also protect fast-growing human cells from such events.