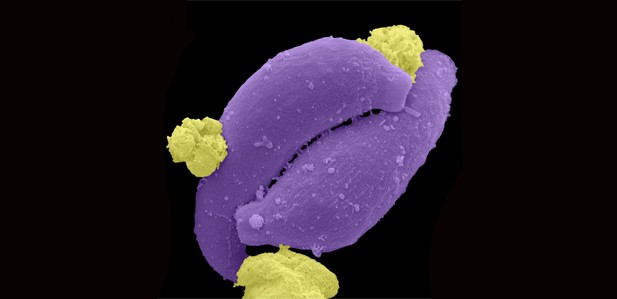

The parasite that causes malaria. Image credit: Leandro Lemgruber, University of Glasgow (CC BY 4.0)

The number of malaria cases has dropped in some Southern Africa countries, but others still remain seriously affected. When people travel within and between countries, they can bring the parasites that cause the disease to different areas. This can fuel local transmission or even lead to outbreaks in a malaria-free area.

When new malaria patients are diagnosed, they are often asked to report their recent travel history, so that the origin of their infection can be tracked. In theory, this would help to spot regions where the disease is imported from, and design targeted interventions.

However, it is difficult to know exactly where the parasites come from based on self-disclosed travel history. At best, this history can provide information about that persons infection but nothing further in the past; at worst this history can be completely incorrect. Parasite DNA, on the other hand, has the potential to bring with it an indelible record of the past. To address the problem of determining where malaria infections came from, Tessema, Wesolowski et al. focused on Northern Namibia, a region where malaria persists despite being practically absent from the rest of the country. Patients movements were assessed using mobile phone call records as well as self-reported travel history In addition, samples a single drop of blood were taken so that the genetic information of the parasites could be examined.

Combining genetic data with travel history and phone records, Tessema, Wesolowski et al. found that, in Northern Namibia, most people had gotten infected by malaria locally. However, the genetic analyses also revealed that certain infections came from places across the Angolan and Zambian borders, information that was much more difficult to obtain using self-report or mobile phone data. A new, separate study by Chang et al. also supports these results, showing that, in Bangladesh, combining genetic data with travel history and mobile phone records helps to track how malaria spreads.

Overall, the work by Tessema, Wesolowski et al. indicate that, in Northern Namibia, it will be necessary to strengthen local interventions to eliminate malaria. However, different countries in the region may also need to coordinate to decrease malaria nearby and reduce the number of cases coming into the country. While genetic data can help to monitor how new malaria cases are imported, this knowledge will be most valuable if it is routinely collected across countries. New tools will also be required to translate genetic data into information that can easily be used for control and elimination programs.