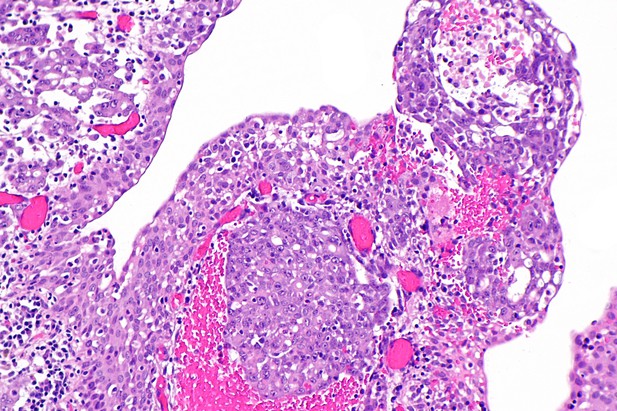

Micrograph of a renal medullary carcinoma. Image credit: Nephron (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC for short) is a rare type of kidney cancer that affects teenagers and young adults. These patients are usually of African descent and carry one of the two genetic changes that cause sickle cell anemia. RMC is an aggressive disease without effective treatments and patients survive, on average, for only six to eight months after their diagnosis.

Recent genetic studies found that most RMC cells have mutations that prevent them from producing a protein called SMARCB1. SMARCB1 normally acts as a so-called tumor suppressor, preventing cells from becoming cancerous. However, it was not clear whether RMCs always have to lose SMARCB1 if they are to survive and grow.

Often, diseases are studied using laboratory-grown cells and tissues that have certain features of the disease. No such models had been created for RMC, which has slowed efforts to understand how the disease develops and find new treatments for it. Hong et al. therefore worked with patients to develop new lines of cells that can be used to study RMC in the laboratory. These RMC cells started dying when they were given copies of the SMARCB1 gene, which supports the theory that RMCs have to lose SMARCB1 in order to grow.

Hong et al. then used a set of genetic reagents that can suppress or delete genes that are targeted by drugs, and followed this by testing a range of drugs on the RMC cells. Drugs and genetic reagents that reduced the activity of the proteasome – the structure inside cells that gets rid of old or unwanted proteins – caused the RMC cells to die. These proteasome inhibitor drugs also killed other kinds of cancer cells with SMARCB1 mutations.

Proteasome inhibitors are already used to treat different types of cancer. Potentially, a clinical trial could be run to see if they will treat patients whose cancers lack SMARCB1. Further work is also needed to determine the exact link between SMARCB1 and the proteasome.