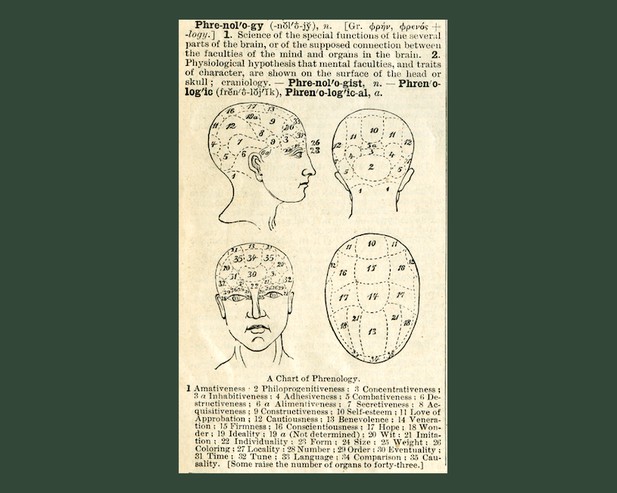

A classical phrenology chart showing the brain divided into numbered regions, each with a supposedly specific function. Image credit: Public domain.

For years, scientists have tried to explain human behavior by measuring brain characteristics. During the first half of the 19th century, craniometry, the science of taking measurements of the skull, was a popular field of research and cognitive abilities as well as many behaviors were associated with different skull sizes and shapes. Although craniometry has been broadly discredited as a science, the study of brain structure and function, and their correlation to human behavior, continues to this day.

Currently, one of the most powerful tools used in the study of the brain is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which relies on strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed imaging. These images can provide functional information, by measuring changes in blood flow to different parts of the brain, as well as structural information such as the amount of gray or white matter or the size of different brain regions. Many studies have shown correlations between functional MRI (fMRI) data and behavioral and demographic traits, such as years of education, lifestyle habits or stress. Another advance in the study of the relationship between behaviors and the brain has been the emergence of better statistical analysis tools thanks to increasing computing power. These tools have made it possible to integrate data from different sources and analyze many variables at the same time, allowing patterns to emerge that would have been previously missed.

Llera et al. have analyzed a large dataset from young healthy volunteers to show that changes in behavioral traits can be predicted by brain structure, and not just by brain function as previously shown. Different types of brain structural data, including what the surface of the brain looks like and relative volumes of gray and white matter, were integrated and analyzed, and correlations between changes in these variables and changes in the demographic and behavioral traits of the subjects were found. Previously, a robust relationship had been established between specific patterns of connections and activity in the brain and a group of characteristics such as life satisfaction, working memory, weight and strength, loneliness, family history of drugs and alcohol use, etc. Llera et al. show that this relationship also holds between the traits and structural brain data. As an example, there is a positive correlation between changes in the number of years of education and the income of the subjects and changes in a pattern of integrated structural data that include the amount of gray matter, white matter integrity and size of specific brain structures. Given these findings it becomes important to reconsider whether differences between individuals previously attributed to brain function could simply explained by the shape or size of the brain and its parts.

These findings show that physical brain characteristics, including its size or the shape of its surface, could predict information such as individuals’ lifestyle decisions or their income; also implying that these characteristics are not simply a product of brain function. The results also demonstrate the power of combining different types of brain data to predict patterns in behavior.