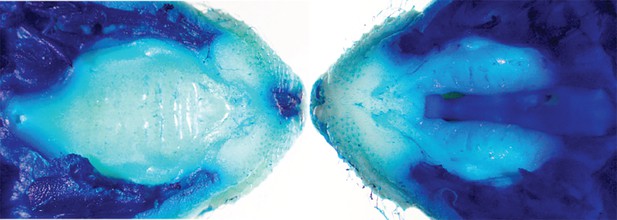

A cleft palate in a Rbfox2 mutant embryo (left) compared to an intact palate in a normal mouse embryo (right). Image credit: Cibi et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Abnormalities affecting the head and face – such as a cleft lip or palate – are among the most common of all birth defects. These tissues normally develop from cells in the embryo known as the neural crest cells, and specifically a subset of these cells called the cranial neural crest cells. Most cases of cleft lip or palate are linked back to genes that affect the biology of this group of cells.

The list of genes implicated in the impaired development of cranial neural crest cells code for proteins with a wide range of different activities. Some encode transcription factors – proteins that switch genes on or off. Others code for chromatin remodeling factors, which control how the DNA is packed inside cells. However, the role of another group of proteins – the splicing factors – remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

When a gene is switched on its genetic code is first copied into a short-lived molecule called a transcript. These transcripts are then edited to form templates to build proteins. Splicing is one way that a transcript can be edited, which involves different pieces of the transcript being cut out and the remaining pieces being pasted together to form alternative versions of the final template. Splicing factors control this process.

Cibi et al. now show that neural crest cells from mice make a splicing factor called Rbfox2 and that deleting this gene for this protein from only these cells leads to mice with a cleft palate and defects in the bones of their head and face.

Further analysis helped to identify the transcripts that are spliced by Rbfox2, and the effects that these splicing events have on gene activity in mouse tissues that develop from cranial neural crest cells. Cibi et al. went on to find a signaling pathway that was impaired in the mutant cells that lacked Rbfox2. Forcing the mutant cells to over-produce one of the proteins involved in this signaling pathway (a protein named Tak1) was enough to compensate for the some of the defects caused by a lack of Rbfox2, suggesting it acts downstream of the splicing regulator.

Lastly, Cibi et al. showed that another protein in this signaling pathway, called TGF-β, acted to increase how much Rbfox2 was made by neural crest cells. Together these findings may be relevant in human disease studies, given that altered TGF-β signaling is a common feature in many birth defects seen in humans.