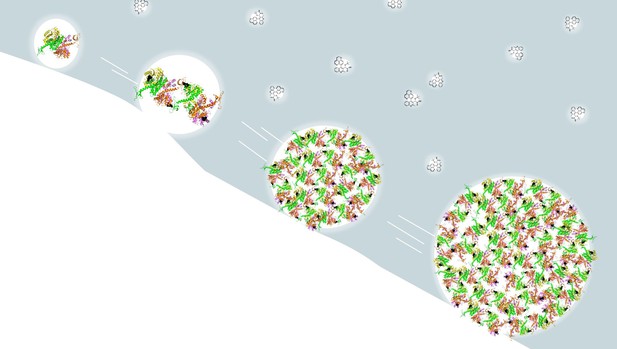

The snowball effect induced by allosteric HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Image credit: Koneru and Kvaratskhelia (CC BY 4.0)

HIV-1 inserts its genetic code into human genomes, turning healthy cells into virus factories. To do this, the virus uses an enzyme called integrase. Front-line treatments against HIV-1 called “integrase strand-transfer inhibitors” stop this enzyme from working. These inhibitors have helped to revolutionize the treatment of HIV/AIDS by protecting the cells from new infections. But, the emergence of drug resistance remains a serious problem. As the virus evolves, it changes the shape of its integrase protein, substantially reducing the effectiveness of the current therapies. One way to overcome this problem is to develop other therapies that can kill the drug resistant viruses by targeting different parts of the integrase protein. It should be much harder for the virus to evolve the right combination of changes to escape two or more treatments at once.

A promising class of new compounds are “allosteric integrase inhibitors”. These chemical compounds target a part of the integrase enzyme that the other treatments do not yet reach. Rather than stopping the integrase enzyme from inserting the viral code into the human genome, the new inhibitors make integrase proteins clump together and prevent the formation of infectious viruses. At the moment, these compounds are still experimental. Before they are ready for use in people, researchers need to better understand how they work, and there are several open questions to answer. Integrase proteins work in groups of four and it is not clear how the new compounds make the integrases form large clumps, or what this does to the virus. Understanding this should allow scientists to develop improved versions of the drugs.

To answer these questions, Koneru et al. first examined two of the new compounds. A combination of molecular analysis and computer modelling revealed how they work. The compounds link many separate groups of four integrases with each other to form larger and larger clumps, essentially a snowball effect. Live images of infected cells showed that the clumps of integrase get stuck outside of the virus’s protective casing. This leaves them exposed, allowing the cell to destroy the integrase enzymes.

Koneru et al. also made a new compound, called (-)-KF116. Not only was this compound able to tackle normal HIV-1, it could block viruses resistant to the other type of integrase treatment. In fact, in laboratory tests, it was 10 times more powerful against these resistant viruses. Together, these findings help to explain how allosteric integrase inhibitors work, taking scientists a step closer to bringing them into the clinic. In the future, new versions of the compounds, like (-)-KF116, could help to tackle drug resistance in HIV-1.