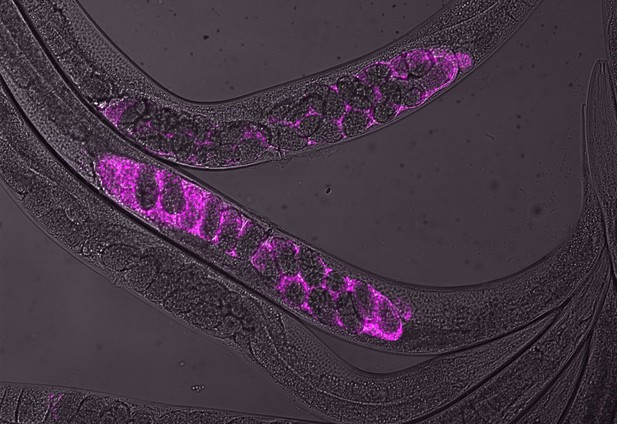

C. elegans hermaphrodites after interacting with males. The worms that have mated successfully have fluorescent male sperm (pink) inside them. Image credit: Lauren N. Booth (CC BY 4.0)

A nematode worm known as Caenorhabditis elegans is often used in the laboratory to study how animals grow and develop. There are two types of C. elegans worm: hermaphrodite individuals produce both female sex cells (eggs) and male sex cells (sperm), while male individuals only produce sperm.

The hermaphrodite worms are able to reproduce without mating with another worm, allowing populations of C. elegans to grow rapidly when they are living in favorable conditions. However, when the hermaphrodites do mate with males they tend to produce more offspring. These offspring are also usually healthier because they receive a mixture of genetic material from two different parents.

Although mating is beneficial for the survival of a species it can also harm an individual animal. Previous studies have shown that mating with male worms can accelerate aging of hermaphrodite worms and cause premature death. However, it remained unclear whether hermaphrodite worms have evolved any mechanisms to protect themselves after mating with a male.

To address this question, Booth et al. used genetic techniques to study the lifespans of hermaphrodite worms. The experiments found that the hermaphrodites’ own sperm (known as self-sperm) regulated a sperm-sensing signaling pathway that protected them from the negative impact of mating with males. Hermaphrodites with self-sperm that mated with males lived for a similar length of time as hermaphrodites that did not mate. On the other hand, hermaphrodites that did not have self-sperm (because they were older or had a genetic mutation) had shorter lifespans after mating than worms that did not mate. Modulating the sperm-sensing signaling pathway in worms that lacked self-sperm was sufficient to protect them from the negative effects of mating with males.

Further experiments found that the hermaphrodites of another nematode worm called C. briggsae – which evolved self-sperm independently of C. elegans – also protected themselves from the negative effects of mating with males in a similar way. This suggests that other animals may also have evolved similar mechanisms to protect themselves from harm when mating.

A separate study by Shi et al. has found that the beneficial effects of self-sperm are mediated by a pathway linked to longevity that also exists in mammals. The results of both investigations combined suggest possible avenues for future research into the complex relationship between health, longevity, and reproduction.