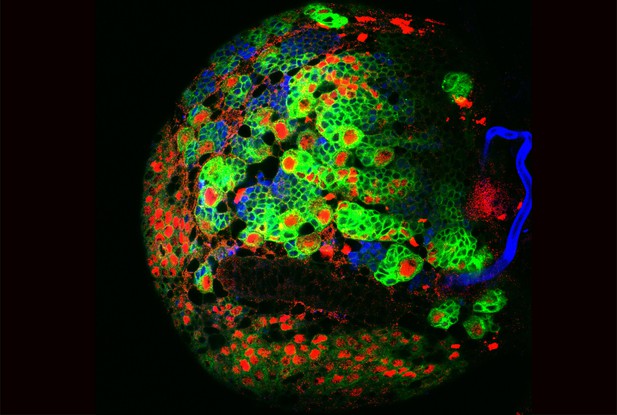

An area in the brain lobe of a developing fruit fly: neural stem cells are marked in red, neurons are marked in blue, cell lineages are depicted in green. Image credit: Abdusselamoglu et al. (CC BY 4.0)

The brain consists of billions of neurons that come in a range of shapes and sizes, with different types of neurons specialized to perform different tasks. Despite their diversity, all of these neurons originate from a single population known as neural stem cells. As the brain develops, each neural stem cell divides to produce two daughter cells: one remains a stem cell, which can then divide again, and the other becomes a neuron.

A longstanding question in developmental biology is how a limited pool of neural stem cells can generate so many different types of neurons. The answer seems to lie in a process known as temporal identity, whereby neural stem cells of different ages give rise to different types of neurons. This requires neural stem cells to keep track of their own age, but it is still unclear how they can do so.

Abdusselamoglu et al. have now uncovered part of the underlying mechanism behind temporal identity by studying fruit flies, an insect in which the early stages of brain development are similar to the ones in mammals. A method was developed to sort fly neural stem cells into groups based on their age. Comparing these groups revealed that a protein called Opa make neural stem cells switch from being 'young' to being 'middle-aged'. Another protein, Osa activates Opa, which in turn represses a protein called Dichaete. As Dichaete is mainly active in young neural stem cells, the actions of Osa and Opa push neural stem cells into middle age.

Fruit flies are therefore a valuable system with which to study the mechanisms that regulate neural stem cell aging. Revealing how the brain generates different types of neurons could help us study the way these cells organize themselves into complex circuits. This knowledge could then be harnessed to understand how these processes go wrong and disrupt development.