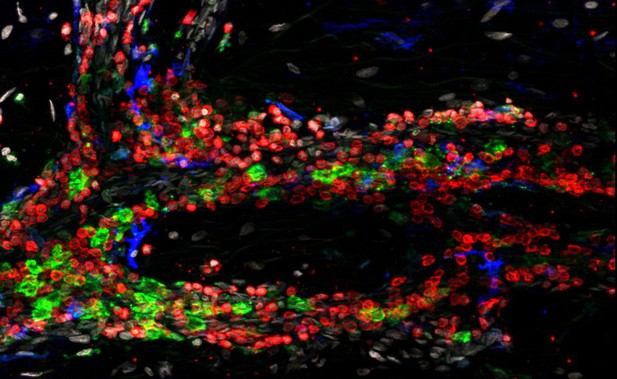

Human skin with a rich network of white blood cells including T cells (red), dendritic cells (green) and macrophages (blue). Image credit: Modified from Xiao-nong Wang, Human Dendritic Cell Laboratory, Newcastle University (CC BY 4.0)

Left unchecked the immune system can cause devastating damage to healthy tissue. To prevent this from happening, immune cells have built-in off switches that dampen their activation. One such switch is a protein called FcγRIIB that sits on the outer surface of immune cells and binds to proteins known as antibodies, which are produced as part of the immune response. Its role is to act as a brake on the immune system, and stop it from getting out of control.

Overactive immune cells can lead to autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, also known as SLE for short, which causes damage to the skin, joints and other organs. Previous work suggests that SLE is correlated with a specific mutation in the FcγRIIB gene, but it is unclear how the mutation and the disease are connected.

Proteins are made out of building blocks called amino acids, which have different chemical properties. A swap of one amino acid for another can have big consequences for the structure of a protein. In the case of FcγRIIB, the mutation that correlates with SLE changes an amino acid called isoleucine for another called threonine. Isoleucine does not mix well with water and is commonly found buried in the middle of proteins or inside cell membranes. Threonine, on the other hand, can readily interact with the hydrogen atoms in water and other amino acids.

Hu, Zhang, Sun et al. used computer simulations and imaged single human cells to find out how the isoleucine to threonine change causes immune cells to become over-activated. The experiments revealed that threonine interacts with a nearby amino acid, putting a kink in the FcγRIIB protein. This kink causes the outer part of the FcγRIIB protein to bend towards the immune cell membrane, stopping it from binding to antibodies, and putting a break on immune cells that have become hyper-activated.

There is currently no cure for SLE, but understanding its causes could take us a step closer to better management of the disease. Small molecule drug treatments often target the three-dimensional shape of certain proteins, so understanding the effect of mutations at the molecular level could help with the design of new treatments in the future.