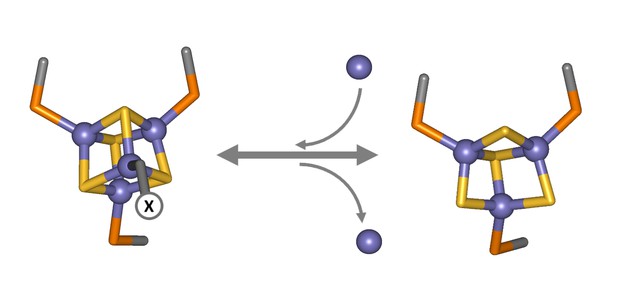

When iron levels are high (left), the iron-sulphur cluster of the RirA protein is fully assembled but it contains a loose iron atom (purple sphere attached to "X"). This atom is captured by other processes when iron levels are low (right), provoking the collapse of the cluster. Image credit: Pellicer Martinez, Crack, Stewart et al., 2019 (CC BY 4.0)

Virtually all life forms require iron to survive, yet too much of the metal can be catastrophic. In healthy cells, many systems regulate this delicate balance. For instance, when a protein called RirA is active in Rhizobium bacteria, it can sense high levels of the metal and helps to shut down the production of proteins that bring in more iron. RirA contains a cluster of four iron and four sulphur atoms, which acts as a sensor for iron availability: however, exactly how this cluster structure detects the levels of the metal in a cell was previously unclear.

Pellicer Martinez, Crack, Stewart et al. used a technique known as time-resolved mass spectrometry to examine the sensory response of the iron-sulphur cluster of RirA when different levels of iron were available. The results revealed a ‘loose’ iron atom in the cluster; when iron levels fall down, this atom is rapidly lost as it is scavenged for use in other essential processes. Without it, the cluster in RirA collapses and the protein becomes inactive. This prompts the cell to produce proteins that enable it to take up iron from its surroundings. Once iron levels are high, RirA can regain its cluster and is active again, stopping the production of proteins that bring in more iron.

Iron-sulphur clusters are common in many proteins, and this work offers new insight into their various roles. It also highlights the potential to use time-resolved mass spectrometry to examine biological processes in depth.