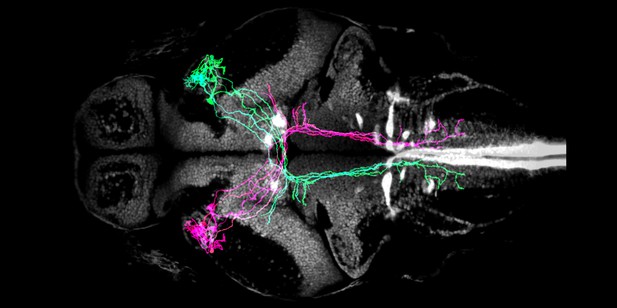

Pretectal neurons in the larval zebrafish brain that control predation. Image credit: Antinucci et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Hunting is an innate behaviour that relies on predators executing a precise set of actions to identify, approach, target, and strike prey. In vertebrates (animals with a backbone), the identity of the brain circuits that trigger hunting is still unclear. These networks are thought to link sensory perception (seeing prey) with a specialised action (starting an attack).

Larval zebrafish are a good model in which to study these circuits, because they have a tiny, transparent brain where neurons can be observed in real time. In addition, it is expected that the networks that control hunting in this species will be preserved across other vertebrates.

To discover these networks, Antinucci et al. genetically engineered zebrafish larvae so that their brain cells would ‘glow’ when they became active. This revealed which individual brain cells would turn on when zebrafish started to hunt. These neurons were in a part of the brain called the pretectum, which receives visual information about prey from the eye.

Next, Antinucci et al. harnessed a technique called optogenetics to artificially turn on these brain cells in the pretectum, which caused the fish to start hunting even when prey was absent. In fact, stimulating just one pretectal cell was enough to trigger the behaviour. Conversely, killing pretectal brain cells using precise laser surgery hindered hunting in zebrafish exposed to prey.

These experiments suggest that pretectal brain cells act like a command centre that controls hunting. They likely play a decision-making role, determining when animals do and do not respond to events in their surroundings. Similar neurons likely control other types of behaviour. Understanding how these circuits work at the cellular level in zebrafish may help scientist study them in other organisms, such as humans.