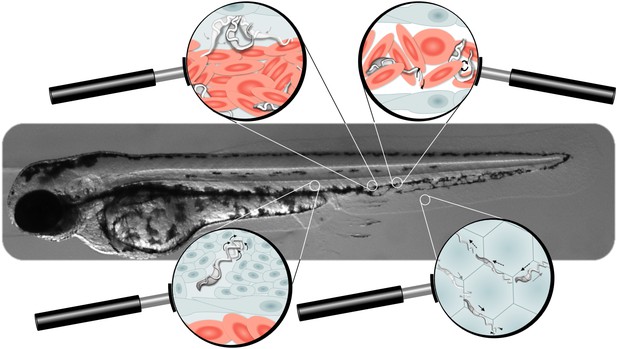

Trypanosome parasites can move through different tissues of an infected zebrafish in various ways. Image credit: Maria Forlenza (CC BY 4.0)

Trypanosomes are one-celled parasites that cause the disease trypanosomiasis, which is also known as sleeping sickness. Trypanosomiasis is transmitted to humans and animals by a type of fly, known as tse-tse, which is commonly found in sub-Saharan Africa. A bite from the tse-tse fly transfers the trypanosome cells into the host’s bloodstream, where they spread from the blood to the internal organs and brain. This leads to a long-term illness, which can sometimes result in a coma and eventually death.

Once in the blood trypanosomes move around using a structure similar to an underwater propeller called the flagellum. How the trypanosomes move and behave in the blood determines how the infection will progress. Until now it has only been possible to observe trypanosomes in plastic dishes or in blood drawn from infected patients. However, neither of these settings mimic the conditions of the bloodstream, and it is currently impossible to look inside human hosts to watch how trypanosomes move.

To overcome this hurdle, Doro et al. infected zebrafish with Trypanosoma carassii, a close relative of the sub-Saharan trypanosomes that specifically infects fish. Zebrafish are transparent when young, making it possible to observe the parasite in the blood and tissues of live fish using a microscope.

Doro et al. noticed that Trypanosoma carassii cells adapt to different environments in the host by using different swimming techniques. For example, in small capillaries trypanosomes were dragged along with the blood flow, whilst in larger vessels, when blood flow was slow or there were fewer red blood cells, trypanosomes actively swam against the current. The parasites were also able to change direction by using their flagella in a ‘whip-like’ motion. Lastly, it was discovered that Trypanosoma carassii could rapidly attach to blood vessel walls using one end of its cell body, even when blood flow was strong. This behaviour may help the parasites escape from the bloodstream into the surrounding tissues, making the infection more dangerous.

Studying how trypanosomes infect zebrafish at this high level of detail provides new insights into how these parasites move and behave inside a host. An important question that remains to be answered, is how exactly the trypanosomes leave the bloodstream. A better understanding of the whole infection process may hint at new ways of fighting these deadly infections in future.