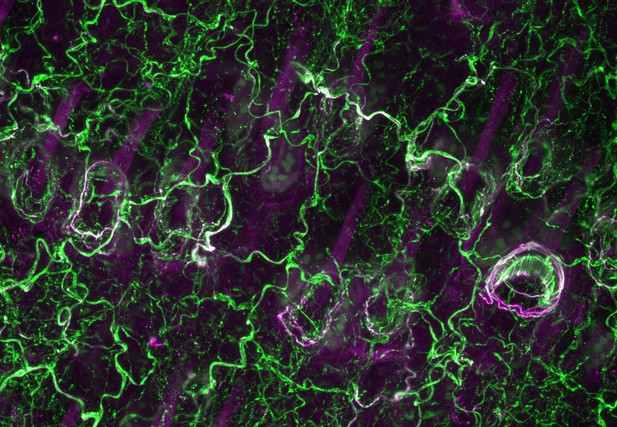

Sensory nerves in skin marked in green and magenta. Image credit: Rose Z. Hill (CC BY 4.0)

Chronic itch is a debilitating disorder that can last for months or years. Eczema, or atopic dermatitis, is the most common cause for chronic itch, affecting one in ten people worldwide. Many treatments for the condition are ineffective, and the exact cause of the disease is unknown, but many different types of cells are likely involved. These include skin cells and inflammation-promoting immune cells, as well as nerve cells that detect inflammation, relay itch and pain information to the brain, and regulate the immune system.

Learning more about how these cells interact in eczema may help scientists find better treatments for the condition. So far, a lot of research has focused on static ‘snapshots’ of mature eczema lesions from human skin or animal models. These studies have identified abnormalities in genes or cells, but have not revealed how these genes and cells interact over time to cause chronic itch and inflammation.

Now, Walsh et al. reveal that immune cells called neutrophils trigger chronic itch in eczema. The experiments involved mice with a condition that mimics eczema, and showed that removing the neutrophils in these mice alleviated their itching. They also showed that dramatic and rapid changes occur in the nervous system of mice suffering from the eczema-like condition. For example, excess nerves grow in the animals’ damaged skin, genes in the nerves that detect sensations become hyperactive, and changes occur in the spinal cord that have been linked to nerve pain. When neutrophils are absent, these changes do not take place.

These findings show that neutrophils play a key role in chronic itch and inflammation in eczema. Drugs that target neutrophils, which are already used to treat other diseases, might help with chronic itch, but they would need to be tested before they can be used on people with eczema.