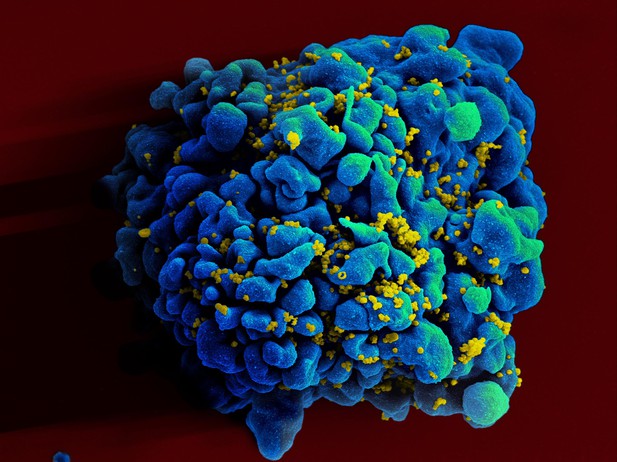

Immune cell infected with HIV. Image credit: NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

Several drugs are available to control HIV, but they do not completely eliminate the virus from the body. Instead, these treatments stop the virus from multiplying, but unless a person is treated very soon after infection, inactive HIV can hide inside cells, and the infection is not completely cleared. Once treatment stops, the inactive virus starts to multiply, reaching pre-treatment levels within weeks. This means that infected individuals must continue treatment for life, or the virus will return and may cause disease. To prevent this, scientists are trying to find a way to eliminate HIV from the body, permanently curing the disease.

Testing HIV drugs is difficult because there is no simple way to determine if all the inactive virus has been removed. One way to test whether a person is cured is to stop treatment, and see if the virus comes back. An alternative method is to measure the amount of inactive HIV present in blood cells. However, Pinkevych et al. have now shown that levels of inactive HIV in the blood may not be a good predictor of whether HIV levels will rebound after treatment.

In the experiments, Pinkevych et al. infected macaques with a monkey version of HIV called simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV for short. The virus was genetically modified to have a ‘genetic barcode’ that allowed researchers to track thousands of individual strains of virus simultaneously . The macaques were then treated with a combination of drugs starting either 4 or 27 days after infection, and then the treatment was stopped to check how rapidly strains of the virus would re-emerge.

Although the virus rebounded in both groups, during treatment the inactive virus was often undetectable in the blood from the group treated four days after infection , suggesting that the virus may be hiding elsewhere. In the group treated 27 days after infection, more blood cells had inactive virus and reactivation was more frequent. However, the amount of inactive virus in the blood did not directly predict the frequency of reactivation: a 100-fold increase in viral levels only led to reactivation being twice as frequent. This suggests that the amount of inactive virus in the blood is not a good read-out for whether the virus will come back.

These experiments suggest that inactive virus hides in cells quickly, since treatment just four days after infection failed to eliminate the virus completely, and that it must hide in cells other than blood cells. Evidence from humans suggests something similar may occur in HIV infection. Further studies may help identify which cells harbor the inactive virus and contribute to infections re-emerging after treatment stops.