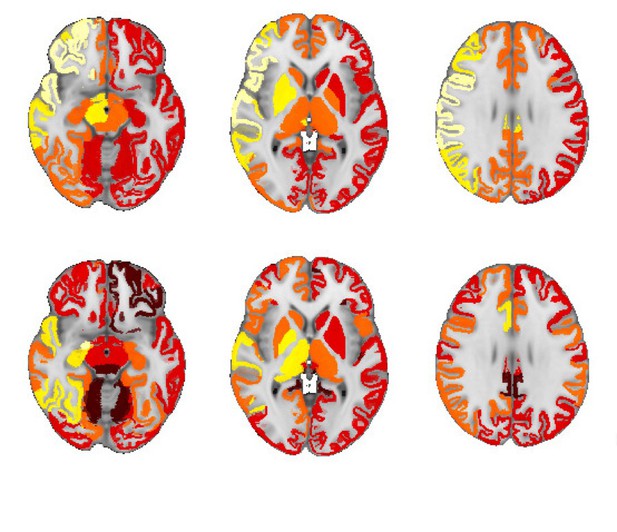

Image showing the average electric field (top panel) and the corresponding changes in the volume (bottom panel) of different regions of the brain following electroconvulsive therapy. Image credit: Miklos Argyelan (CC BY 4.0)

Electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT for short, can be an effective treatment for severe depression. Many patients who do not respond to medication find that their symptoms improve after ECT. During an ECT session, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and two electrodes are attached to the scalp to produce an electric field that generates currents within the brain. These currents activate neurons and make them fire, causing a seizure, but it remains unclear how this reduces symptoms of depression.

For many years, researchers thought that the induced seizure must be key to the beneficial effects of ECT, but recent studies have cast doubt on this idea. They show that increasing the strength of the electric field alters the clinical effects of ECT, without affecting the seizure. This suggests that the benefits of ECT depend on the electric field itself.

Argyelan et al. now show that electric fields affect the brain by making a part of the brain known as the gray matter expand. In a large multinational study, 151 patients with severe depression underwent brain scans before and after a course of ECT. The scans revealed that the gray matter of the patients’ brains expanded during the treatment. The patients who experienced the strongest electric fields showed the largest increase in brain volume, and individual brain areas expanded if the electric field within them exceeded a certain threshold. This effect was particularly striking in two areas, the hippocampus and the amygdala. Both of these areas are critical for mood and memory.

Further studies are needed to determine why the brain expands after ECT, and how long the effect lasts. Another puzzle is why the improvements in depression that the patients reported after their treatment did not correlate with changes in brain volume. Disentangling the relationships between ECT, brain volume and depression will ultimately help develop more robust treatments for this disabling condition.