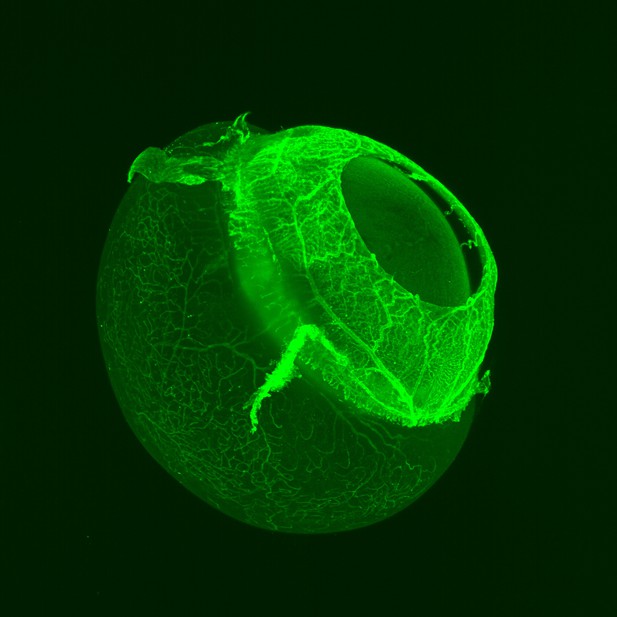

Mouse eyeball taken with light-sheet fluorescent microscopy, with the blood vessels shown in green. Image credit: Claudia Prahst (CC BY 4.0)

Eye diseases affect millions of people worldwide and can have devasting effects on people’s lives. To find new treatments, scientists need to understand more about how these diseases arise and how they progress. This is challenging and progress has been held back by limitations in current techniques for looking at the eye. Currently, the most commonly used method is called confocal imaging, which is slow and distorts the tissue. Distortion happens because confocal imaging requires that thin slices of eye tissue from mice used in experiments are flattened on slides; this makes it hard to accurately visualize three-dimensional structures in the eye.

New methods are emerging that may help. One promising method is called light-sheet fluorescent microscopy (or LSFM for short). This method captures three-dimensional images of the blood vessels and cells in the eye. It is much faster than confocal imaging and allows scientists to image tissues without slicing or flattening them. This could lead to more accurate three-dimensional images of eye disease.

Now, Prahst et al. show that LSFM can quickly produce highly detailed, three-dimensional images of mouse retinas, from the smallest parts of cells to the entire eye. The technique also identified new features in a well-studied model of retina damage caused by excessive oxygen exposure in young mice. Previous studies of this model suggested the disease caused blood vessels in the eye to balloon, hinting that drugs that shrink blood vessels would help. But using LSFM, Prahst et al. revealed that these blood vessels actually take on a twisted and knotted shape. This suggests that treatments that untangle the vessels rather than shrink them are needed.

The experiments show that LSFM is a valuable tool for studying eye diseases, that may help scientists learn more about how these diseases arise and develop. These new insights may one day lead to better tests and treatments for eye diseases.