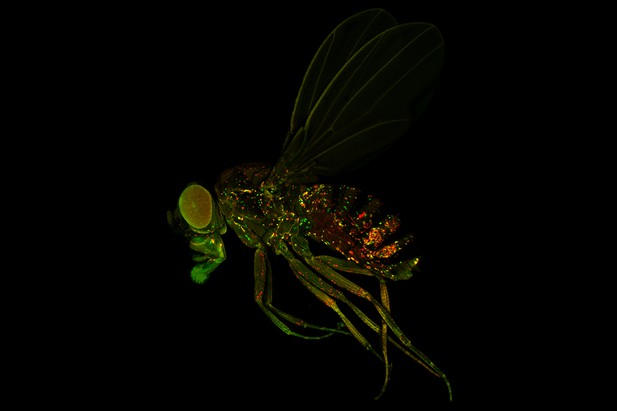

Microscopy image of an adult fruit fly showing which immune cells (green) have been metabolically activated (red). Image credit: Gabriela Krejčová and Adam Bajgar (CC BY 4.0)

Macrophages are the immune system's first line of defense against infection. These immune cells can be found in all tissues and organs, watching for signs of disease-causing agents and targeting them for destruction. Maintaining macrophages costs energy, so to minimize waste, these cells spend most of their lives in 'low power mode'. When macrophages sense harmful bacteria, they rapidly awaken and trigger a series of immune events that protect the body from infection. However, to perform these protective tasks macrophages need a sudden surge in energy.

In mammals, activated macrophages get their energy from aerobic glycolysis – a series of chemical reactions normally reserved for low oxygen environments. Switching on this metabolic process requires a protein called hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1 α), which switches on the genes that macrophages need to generate energy as quickly as possible. Macrophages then maintain their energy supply by sending out chemical signals which divert glucose away from the rest of the body.

Fruit flies are regularly used as a model system for studying human disease, as the mechanisms they use to defend themselves from infections are similar to human immune cells. However, it remains unclear whether their macrophages undergo the same metabolic changes during an infection.

To address this question, Krejčová et al. isolated macrophages from fruit flies that had been infected with bacteria. Experiments studying the metabolism of these cells revealed that, just like human macrophages, they responded to bacteria by taking in more glucose and generating energy via aerobic glycolysis. The macrophages of these flies were also found to draw in energy from the rest of the body by raising blood sugar levels and depleting stores of glucose. Similar to human macrophages, these metabolic changes depended on HIF1α, and flies without this protein were unable to secure the level of energy needed to effectively fight off the bacteria.

These findings suggest that this metabolic switch to aerobic glycolysis is a conserved mechanism that both insects and mammals use to fight off infections. This means in the future fruit flies could be used as a model organism for studying diseases associated with macrophage mis-activation, such as chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases.