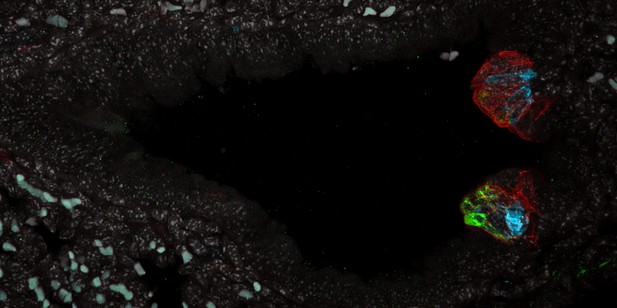

Genetically removing Jag ligands in the developing airway has no effect on the number of neuroendocrine cells (in blue) or the associated secretory cells (in red and green) but results in an inability to form secretory cells elsewhere (areas in gray). Image credit: Maria Stupnikov (CC BY 4.0)

Cells communicate with each other by sending messages through a range of signaling pathways. One of the ways cells signal to each other is through a well-studied pathway known as Notch. In this pathway, cells display molecules on their surface, known as Notch ligands, that can activate Notch receptor proteins on the surface of neighboring cells. Once the Notch receptors bind to these ligands, they trigger various responses inside the cell. Notch ligands exist in two different families: Delta-like (Dll) ligands and Jagged (Jag) ligands.

The layer of cells that lines the airways in the lungs consists of several different cell types. These include secretory cells that produce the fluid covering the airway surface, multiciliated cells, and neuroendocrine cells. Together these cells work as a barrier to protect the lung from environmental particles that may be breathed in. Additionally, the lung also has multipotent progenitor cells, which can become any of the other types.

When Notch signaling is missing from the lung during embryonic development, not enough secretory cells are made, while other cell types are made in excess. This is because the multipotent progenitor cells need to communicate via Notch signaling to decide what type of cell to become and keep the right proportion of different cell types in the airways. In other organs, multipotent progenitors can become different types of cells depending on whether Notch signaling was activated by Dll or by Jag ligands, but it was unknown if this also happened in the lungs.

Stupnikov et al. investigated the situation in the airways during development by looking at where and when Dll and Jag ligands first appeared, and by inactivating the genes that code for these ligands. They found that Jag ligands appeared well before Dll ligands, and that when the genes coding for Jag ligands were inactivated, more ciliated cells were produced. By contrast, loss of Dll ligands resulted in an increase in the neuroendocrine and their associated secretory cells, with little effect on the multiciliated cells. This increase resembled what is seen in some human diseases.

The results suggest that the diversity of Notch effects in the airways depends on which Notch ligand is locally available. These observations may help to understand the mechanism of certain diseases involving neuroendocrine cells in the lung, such as small cell carcinoma or bronchial carcinoid tumors.