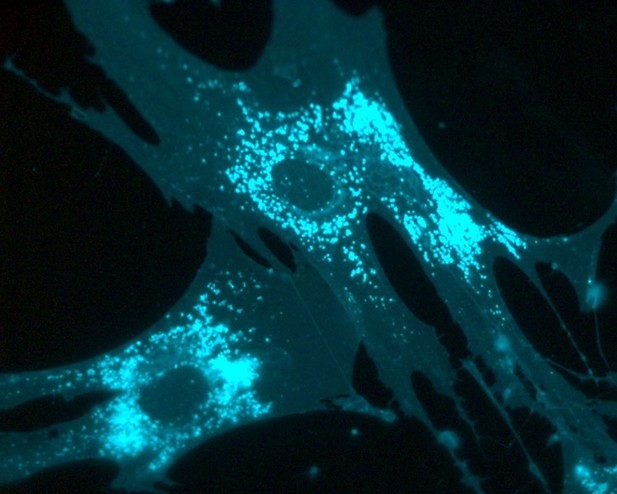

Fibroblasts from patients that lack NPC2 showing excessive cholesterol accumulation (cholesterol is shown in cyan). Image credit: Leslie A. McCauliff (CC BY 4.0)

Cholesterol is a type of fat that is essential for many processes in the body, such as repairing damaged cells and producing certain hormones. Normally, cholesterol enters cells from the bloodstream and is then moved to the parts of the cell that need it via a process known as ‘trafficking’.

When cholesterol trafficking goes wrong, abnormally large amounts of cholesterol and other fats accumulate within the cell. Over time, these fatty deposits become toxic to cells and eventually damage the affected tissues. Niemann-Pick type C disease (NPC) is a severe genetic disorder affecting cholesterol trafficking. It is characterized by cholesterol build-up in multiple tissues, including the brain, which ultimately causes degeneration and death of nerve cells.

Two proteins, NPC1 and NPC2, are involved in NPC disease. Both proteins normally help move cholesterol out of important trafficking compartments (known as the endosomal and lysosomal compartments) to other areas of the cell where it is needed. Patients with the disease can have mutations in either the gene for NPC1 or the gene for NPC2. This means that cells from NPC1 patients do not make enough functional NPC1 protein (but contain working NPC2), and vice versa.

Previous studies had shown that giving cells with NPC1 mutations large amounts of the small molecule lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA for short) could compensate for the loss of NPC1, and stop the toxic build-up of cholesterol. McCauliff, Langan, Li et al. therefore wanted to explore exactly how LBPA was doing this. They had shown that LBPA dramatically increased the ability of purified NPC2 protein to transport cholesterol, and wondered if the effect of LBPA in the cells without NPC1 depended on NPC2. They predicted that boosting LBPA levels would not work in cells lacking NPC2.

Biochemical experiments using purified protein showed that LBPA and NPC2 did indeed interact directly with each other. Systematically changing different building blocks of NPC2 revealed that a single region of the protein is sensitive to LBPA, and when this region was altered, LBPA could no longer interact with NPC2. Since LBPA is naturally produced by cells, they then stimulated cells grown in the laboratory to generate more LBPA using its precursor phosphatidylglycerol. They used cells from patients with mutations in either NPC1 or NPC2 and demonstrated that LBPA’s ability to reverse the accumulation of cholesterol was dependent on its interaction with NPC2. Thus, increasing LBPA levels in cells from patients with NPC1 mutations was beneficial, but had no effect on cells from patients with NPC2 mutations.

These results shed new light not only on how cells transport cholesterol, but also on potential methods to combat disorders of cellular cholesterol trafficking. In the future, LBPA could be developed as a genetically tailored, patient-specific therapy for diseases like NPC.