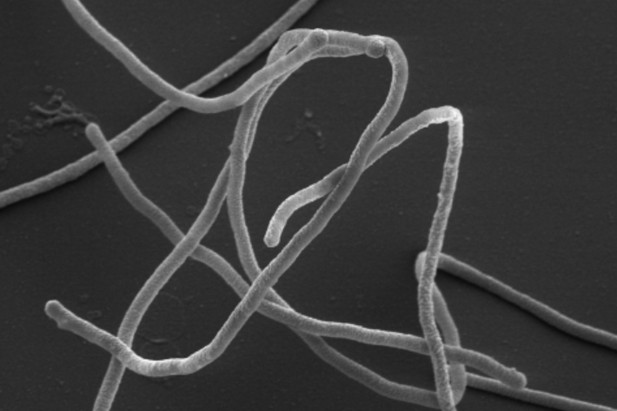

Scanning electron micrograph of M. ruber. Image credit: Tindall et al., 2010, Stand Genomic Sci (CC BY 2.5)

Electrical signals in the brain and muscles allow animals – including humans – to think, make memories and move around. Cells generate these signals by enabling charged particles known as ions to pass through the physical barrier that surrounds all cells, the cell membrane, at certain times and in certain locations.

The ions pass through pores made by various channel proteins, which generally have so-called “selectivity filters” that only allow particular types of ions to fit through. For example, the selectivity filters of a family of channels in mammals known as the Cavs only allow calcium ions to pass through. Another family of ion channels in mammals are similar in structure to the Cavs but their selectivity filters only allow sodium ions to pass through instead of calcium ions.

Ion channels are found in all living cells including in bacteria. It is thought that the Cavs and sodium-selective channels may have both evolved from Cav-like channels in an ancient lifeform that was the common ancestor of modern bacteria and animals. Previous studies in bacteria found that modifying the selectivity filters of some sodium-selective channels known as BacNavs allowed calcium ions to pass through the mutant channels instead of sodium ions. However, no Cav channels had been identified in bacteria so far, representing a missing link in the evolutionary history of ion channels.

Shimomura et al. have now found a Cav-like channel in a bacterium known as Meiothermus ruber. Like all proteins, ion channels are made from amino acids and comparing the selectivity filter of the M. ruber Cav with those of mammalian Cavs and the calcium-selective BacNav mutants from previous studies revealed one amino acid that plays a particularly important role. This amino acid is a glycine that helps select which ions may pass through the pore and is also present in the selectivity filters of many Cavs in mammals.

Together these findings suggest that the Cav channel from M. ruber is similar to the mammal Cav channels and may more closely resemble the Cav-like channels thought to have existed in the common ancestor of bacteria and animals. Since other channel proteins from bacteria are useful genetic tools for studies in human and other animal cells, the Cav channel from M. ruber has the potential to be used to stimulate calcium signaling in experiments.