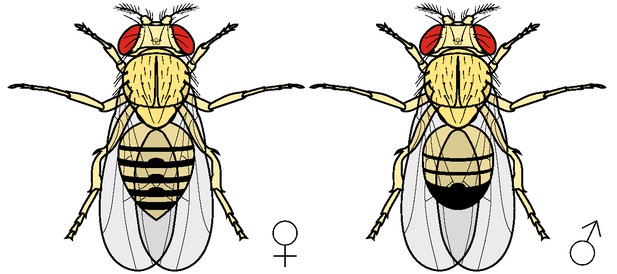

Male and female fruit flies. Image credit: Public domain

Male and female animals of the same species sometimes differ in appearance and sexual behavior, a phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism. Both sexes share most of the same genes, but differences can emerge because of the way these are read by cells to create proteins – a process called gene expression. For instance, certain genes can be more expressed in males than in females, and vice-versa.

Most studies into the emergence of sexual dimorphism have taken place in stable environments with few changes in climate or other factors. Therefore, the potential impact of environmental changes on sexual dimorphism has been largely overlooked.

Here, Hsu et al. used genetic and computational approaches to investigate whether male and female fruit flies adapt differently to a new, hotter environment over several generations. The experiment showed that, after only 100 generations, the way that 60% of all genes were expressed evolved in a different direction in the two sexes. This led to differences in how the males and females made and broke down fat molecules, and in how their neurons operated. These expression changes also translated in differences for high-level biological processes. For instance, animals in the new settings ended up behaving differently, with the males at the end of the experiment spending more time chasing females than the ancestral flies.

These findings demonstrate that male and female fruit flies adapt many biological processes (including metabolism and behaviors) differently to cope with changes in their environment, and that many different genes support these sex-specific adaptations. Ultimately, the work by Hsu et al. may inform medical strategies that take into account interactions between the patient’s sex and their environment.