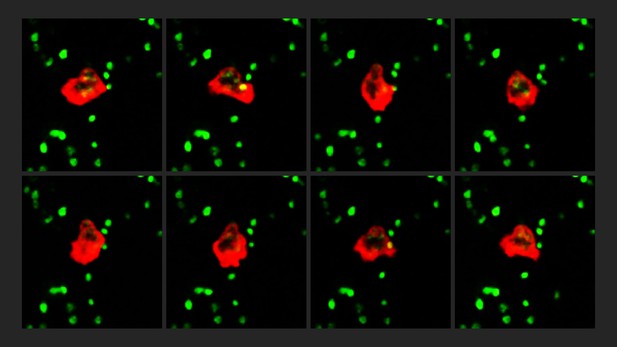

Frames (represented by individual panels) from a time-lapse showing the position of a neutrophil (red) changing as it interacts with ‘primed’ platelets (green). Image credit: Adela Constantinescu-Bercu (CC BY 4.0)

Platelets in our blood form clots over sites of injury to stop us from bleeding. Blood clots can also occur in places where they are not needed, such as deep veins in our legs or other regions of the body. Developing such clots – also known as deep vein thrombosis (or DVT for short) – is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases and a major cause of death. Although certain inherited factors have been linked to DVT, the underlying mechanisms of the disease remain poorly understood.

In addition to platelets, the pathological (or dangerous) clots that cause DVT also contain immune cells called neutrophils which fight off bacterial infections. Platelets are recruited to the wall of the vein by a protein called “von Willebrand Factor” (or VWF for short). However, it remained unclear how these recruited platelets interact with neutrophils and whether this promotes the onset of DVT.

To answer this question, Constantinescu-Bercu et al. used a device that mimics the flow of blood to study how human platelets change when they are exposed to VWF. This revealed that VWF ‘primes’ the platelets to interact with neutrophils via a protein called integrin αIIbβ3. Further experiments showed that integrin αIIbβ3 binds to a protein on the surface of neutrophils called SLC44A2. Once the neutrophils interacted with the ‘primed’ platelets, they started making traps which increased the size of the blood clot by capturing other blood cells and proteins.

Finally, Constantinescu-Bercu et al. studied a genetic variant of the SLC44A2 protein which is found in 22% of people and is associated with a lower risk of developing DVT. This genetic mutation caused SLC44A2 to interact with ‘primed’ platelets more weakly, which may explain why people with this genetic variant are protected from getting DVT.

These findings suggest that blocking the interaction between ‘primed’ platelets and neutrophils could reduce the risk of DVT. Although current treatments for DVT can prevent patients from forming dangerous blood clots, they can also cause severe bleeding. Since neutrophils are not crucial for normal blood clots to form at the site of injury, drugs targeting SLC44A2 could inhibit inappropriate clotting without causing excess bleeding.