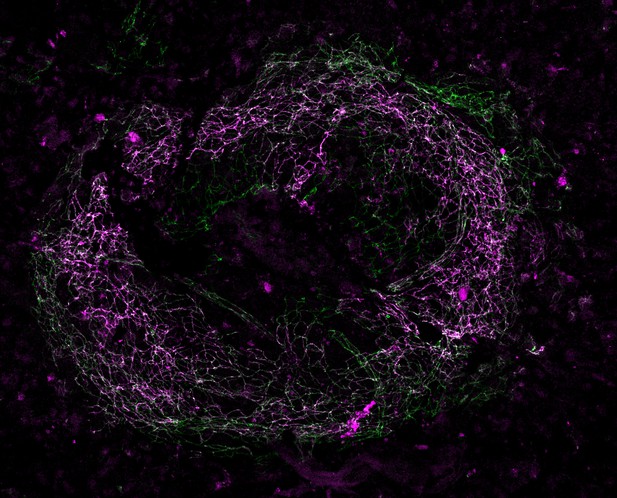

Image shows proteins marking blood vessels in general (green) and specifically leaky blood vessels (magenta), in the eye of a wild-type mouse that has been injured with a laser. Image credit: Ross Smith (CC BY 4.0)

The number of people with impaired vision and blindness is increasing in Western society due to the aging population and the increased prevalence of diabetes. This has led to eye diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy becoming more common. In both these eye diseases, new blood vessels grow in the retina – the light-sensitive part of the eye – to bring oxygen and nutrients to the tissue. However, these new blood vessels are leaky and allow molecules to leave the bloodstream and enter the retinal tissue. This causes the retina to swell and impair a person’s vision. The leaky blood supply also reduces the amount of oxygen that gets to the tissue, resulting in further damage to the retina.

When tissues experience low levels of oxygen, cells start making a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (or VEGF for short). Whilst this protein is important for helping form new blood vessels, it also makes these vessels leaky. Current treatments for age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy decrease swelling in the eye by blocking the action of VEGF. However, these treatments also cause existing blood vessels and nerve cells to die, leading to irreversible damage. Now, Smith et al. have set out to find whether the effects of VEGF can be blocked without causing further damage to existing cells.

To investigate this possibility, the eyes and retinas of mice were treated with a laser or exposed to changing oxygen levels to create injuries that resembled human age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. Each of the tested mice had specific mutations in proteins known to interact with VEGF. Fluorescent particles were injected into the bloodstream of the mice to assess how these different mutations affected blood vessel leakage: if fluorescent particles could no longer be detected outside the blood vessels, this suggested that the mutation had stopped the vessels from leaking. Further experiments showed these specific mutations affected leakage and did not prevent new blood vessels from forming.

In the future it will be important to see if drugs, rather than mutations, can also decrease the leakiness of blood vessels in the retina. Such chemical compounds could then be tested in mouse experiments. If successful, these drugs might be used to treat patients with age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.