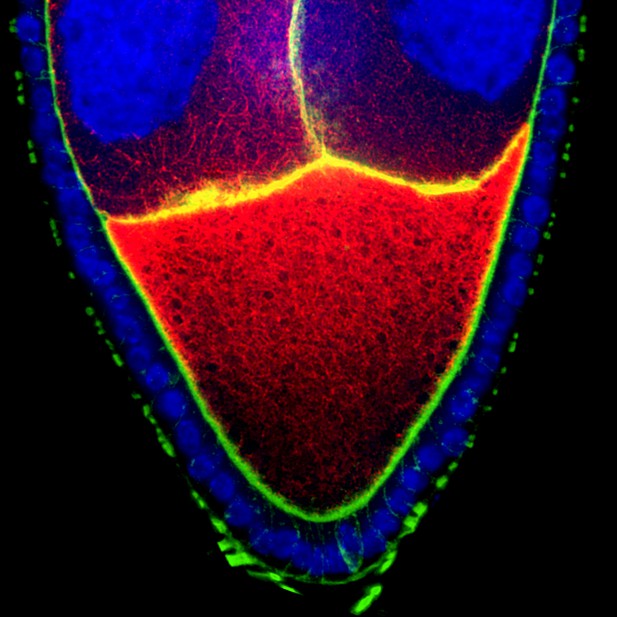

Microtubules (red) are more dense at one end of the egg cell while microfilaments (green) are localized uniformly beneath the membrane. Image credit: Wen Lu (CC BY 4.0)

One of the most fundamental steps of embryonic development is deciding which end of the body should be the head, and which should be the tail. Known as 'axis specification', this process depends on the location of genetic material called mRNAs. In fruit flies, for example, the tail-end of the embryo accumulates an mRNA called oskar. If this mRNA is missing, the embryo will not develop an abdomen.

The build-up of oskar mRNA happens before the egg is even fertilized and depends on two types of scaffold proteins in the egg cell called microtubules and microfilaments. These scaffolds act like ‘train tracks’ in the cell and have associated protein motors, which work a bit like trains, carrying cargo as they travel up and down along the scaffolds. For microtubules, one of the motors is a protein called kinesin-1, whereas for microfilaments, the motors are called myosins.

Most microtubules in the egg cell are pointing away from the membrane, while microfilament tracks form a dense network of randomly oriented filaments just underneath the membrane. It was already known that kinesin-1 and a myosin called myosin-V are important for localizing oskar mRNA to the posterior of the egg. However, it was not clear why the mRNA only builds up in that area.

To find out, Lu et al. used a probe to track oskar mRNA, while genetically manipulating each of the motors so that their ability to transport cargo changed. Modulating the balance of activity between the two motors revealed that kinesin-1 and myosin-V engage in a tug-of-war inside the egg: myosin-V tries to keep oskar mRNA underneath the membrane of the cell, while kinesin-1 tries to pull it away from the membrane along microtubules. The winner of this molecular battle depends on the number of microtubule tracks available in the local area of the cell. In most parts of the cell, there are abundant microtubules, so kinesin-1 wins and pulls oskar mRNA away from the membrane. But at the posterior end of the cell there are fewer microtubules, so myosin-V wins, allowing oskar mRNA to localize in this area. Artificially 'shaving' some microtubules in a local area immediately changed the outcome of this tug-of-war creating a build-up of oskar mRNA in the 'shaved' patch.

This is the first time a molecular tug-of-war has been shown in an egg cell, but in other types of cell, such as neurons and pigment cells, myosins compete with kinesins to position other molecular cargoes. Understanding these processes more clearly sheds light not only on embryo development, but also on cell biology in general.