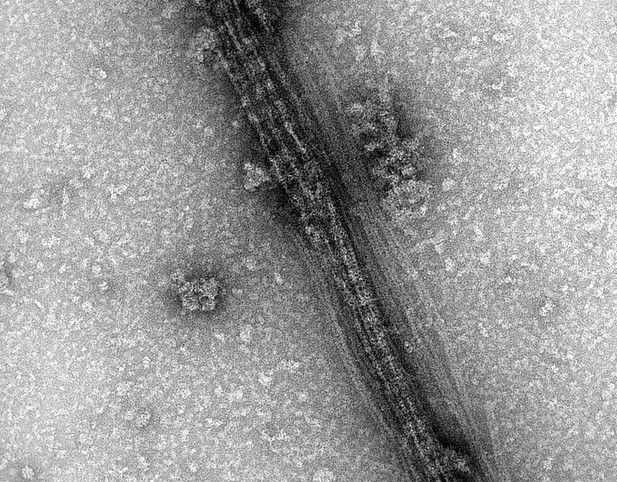

Microscopy image showing a bundle of septin filaments formed in a test tube from yeast septin complexes containing six subunits that were synthesized in the presence of guanidinium. Image credit: Aurélie Bertin (CC BY 4.0)

For a cell to work and perform its role, it relies on molecules called proteins that are made up of chains of amino acids. Individual proteins can join together like pieces in a puzzle to form larger, more complex structures. How the protein subunits fit together depends on their individual shapes and sizes.

Many cells contain proteins called septins, which can assemble into larger protein complexes that are involved in range of cellular processes. The number of subunits within these complexes differs between organisms and sometimes even between cell types in the same organism. For example, yeast typically have eight subunits within a septin protein complex and struggle to survive when the number of septin subunits is reduced to six. Whereas other organisms, including humans, can make septin protein complexes containing six or eight subunits. However, it is poorly understood how septin proteins are able to organize themselves into these different sized complexes.

Now, Johnson et al. show that a chemical called guanidinium helps yeast make complexes containing six septin subunits. Guanidinium has many similarities to the amino acid arginine. Comparing septins from different species revealed that one of the septin proteins in yeast lacks a key arginine component. This led Johnson et al. to propose that when guanidinium binds to septin at the site where arginine should be, this steers the septin protein towards the shape required to make a six-subunit complex.

These findings reveal a new detail of how some species evolved complexes consisting of different numbers of subunits. This work demonstrates a key difference between complexes made up of six septin proteins and complexes which are made up of eight, which may be relevant in how different human cells adapt their septin complexes for different purposes. It may also become possible to use guanidinium to treat genetic diseases that result from the loss of arginine in certain proteins.