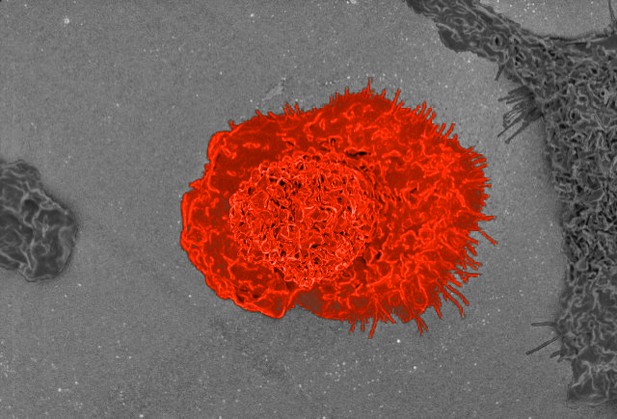

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a macrophage. Image credit: NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

Air pollution is a major global health problem that causes around 4.2 million deaths each year. Once inhaled, pollution particles can remain in the lungs, where they cause inflammation, tissue damage, and ultimately chronic disease. Macrophages, a population of immune cells in the lungs, are involved in this inflammatory process.

Itaconate is a molecule with potential anti-inflammatory effects, produced by mammalian cells including macrophages. Recent studies have shown that a modified form of the molecule, 4-octyl itaconate, reduces inflammation when applied to cells exposed to lipopolysaccharide, a component of infectious bacteria that is, usually, a strong trigger of inflammation. These experiments used the 4-octyl modification to ensure that itaconate could get into the cells.

Itaconate’s anti-inflammatory action is thought to work by activating a signaling process in cells called the NRF2 pathway. NRF2 is a protein made by ‘active’ macrophages, that is, macrophages already primed to respond to foreign particles. NRF2 in turn increases production of factors that ‘damp down’ inflammation, all of which are collectively termed the NRF2 anti-inflammatory pathway. Although macrophages in the lungs are linked with inflammation caused by air pollution, their role – and that of itaconate – is still not well-understood. Sun et al. therefore wanted to determine if itaconate helps macrophages control pollution-induced inflammation.

Initial experiments treated mouse macrophage cells with pollution particles. Analyzing gene activity in these cells showed that exposure to pollution did indeed switch on the Acod1 gene, which encodes the enzyme that makes itaconate. It also turned on genes for other molecules involved in inflammation. Pre-treating macrophages with 4-octyl itaconate before pollution exposure reduced inflammation and also, as expected, turned on the NRF2 pathway.

To determine whether cells’ own production of itaconate affected lung inflammation, macrophages were isolated from mutant mice lacking Acod1. Comparing these cells, which could not make itaconate, with normal cells revealed that removing itaconate did not change the inflammatory response to pollution. Activity of the NRF2 pathway also remained similar in both types of cells. This showed that itaconate produced by macrophages likely has different effects on lung inflammation from other forms of the compound.

These findings represent a step forward in understanding how pollution interacts with immune cells in the lungs. They reveal that the source of anti-inflammatory factors can be just as important in shaping immune responses as the type of factor. These results highlight the need for further, detailed work on the mechanisms underlying pollution-induced disease.