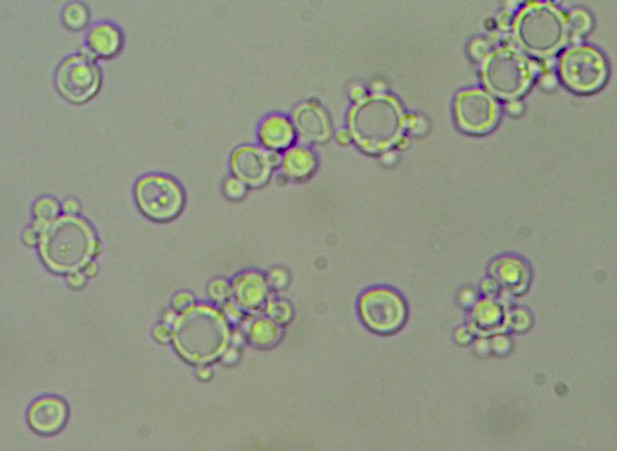

Torulaspora globosa, one of the yeast species that contains WHO genes. Image credit: Lisa Lombardi (CC BY 4.0)

In the same way as a sperm from a male and an egg from a female join together to form an embryo in most animals, yeast cells have two sexes that coordinate how they reproduce. These are called “mating types” and, rather than male or female, an individual yeast cell can either be mating type “a” or “alpha”. Every yeast cell contains the genes for both mating types, and each cell’s mating type is determined by which of those genes it has active.

Only one mating type gene can be ‘on’ at a time, but some yeast species can swap mating type on demand by switching the corresponding genes ‘on’ or ‘off’. This switch is unusual. Rather than simply activate one of the genes it already has, the yeast cell keeps an inactive version of each mating type gene tucked away, makes a copy of the gene it wants to be active and pastes that copy into a different location in its genome. To do all of this yeast need another gene called HO. This gene codes for an enzyme that cuts the DNA at the location of the active mating type gene. This makes an opening that allows the cell to replace the ‘a’ gene with the ‘alpha’ gene, or vice versa. This system allows yeast cells to continue mating even if all the cells in a colony start off as the same mating type. But, cutting into the DNA is risky, and can damage the health of the cell. So, why did yeast cells evolve a system that could cause them harm?

To find out where the HO gene came from, Coughlan et al. searched through all the available genomes from yeast species for other genes with similar sequences and identified a cluster which they nicknamed “weird HO” genes, or WHO genes for short. Testing these genes revealed that they also code for enzymes that make cuts in the yeast genome, but the way the cell repairs the cuts is different. The WHO genes are jumping genes. When the enzyme encoded by a WHO gene makes a cut in the genome, the yeast cell copies the gene into the gap, allowing the gene to ‘jump’ from one part of the genome to another. It is possible that this was the starting point for the evolution of the HO gene. Changes to a WHO gene could have allowed it to cut into the mating type region of the yeast genome, giving the yeast an opportunity to ‘domesticate’ it. Over time, the yeast cell stopped the WHO gene from jumping into the gap and started using the cut to change its mating type.

Understanding how cells adapt genes for different purposes is a key question in evolutionary biology. There are many other examples of domesticated jumping genes in other organisms, including in the human immune system. Understanding the evolution of HO not only sheds light on how yeast mating type switching evolved, but on how other species might harness and adapt their genes.