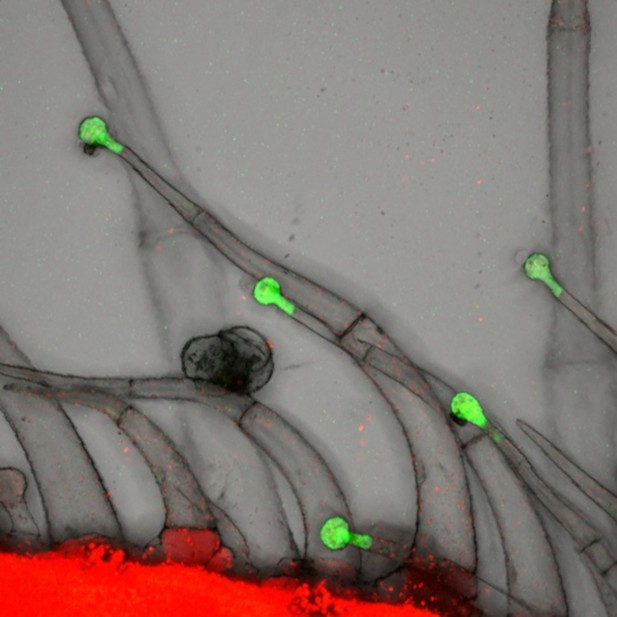

Tomato hair cells expressing a green fluorescent protein at the site where acylsugars are synthesized. Image credit: Pengxiang Fan (CC BY 4.0)

Plants produce a vast variety of different molecules known as secondary or specialized metabolites to attract pollinating insects, such as bees, or protect themselves against herbivores and pests. The secondary metabolites are made from simple building blocks that are readily available in plants, including amino acids, fatty acids and sugars.

Different species of plant, and even different parts of the same plant, produce their own sets of secondary metabolites. For example, the hairs on the surface of tomatoes and other members of the nightshade family of plants make metabolites known as acylsugars. These chemicals deter herbivores and pests from damaging the plants.

To make acylsugars, the plants attach long chains known as fatty acyl groups to molecules of sugar, such as sucrose. Some members of the nightshade family produce acylsugars with longer chains than others. In particular, acylsugars with long chains are only found in tomatoes and other closely-related species. It remained unclear how the nightshade family evolved to produce acylsugars with chains of different lengths.

To address this question, Fan et al. used genetic and biochemical approaches to study tomato plants and other members of the nightshade family. The experiments identified two genes known as AACS and AECH in tomatoes that produce acylsugars with long chains. These two genes originated from the genes of older enzymes that metabolize fatty acids – the building blocks of fats – in plant cells. Unlike the older genes, AACS and AECH were only active at the tips of the hairs on the plant’s surface. Fan et al. then investigated the evolutionary relationship between 11 members of the nightshade family and two other plant species. This revealed that AACS and AECH emerged in the nightshade family around the same time that longer chains of acylsugars started appearing.

These findings provide insights into how plants evolved to be able to produce a variety of secondary metabolites that may protect them from a broader range of pests. The gene cluster identified in this work could be used to engineer other species of crop plants to start producing acylsugars as natural pesticides.